Magnified riflescopes use reticles to provide an aiming reference relative to their target. In today’s world of modern optics, riflescope reticles can be either stone simple, like Trijicon’s Triangle Post reticle or quite sophisticated such as the Horus Vision TREMOR 3. One could write entire books about the differences in rifle scope reticles, stadia lines and the manner in which reticles have subtensions at various distances with respective units of angular measurement. However, casting aside any reticle’s unique style or complexity, the reticle itself can only be manufactured in certain ways. Typically, reticles are etched directly onto a layer of optical glass and these etched pieces of glass can only sit in two places inside the scope body. The result is that this positioning brings forth nuances in shooting which can be critical to connecting with targets, especially at distance.

Inside A Modern Riflescope

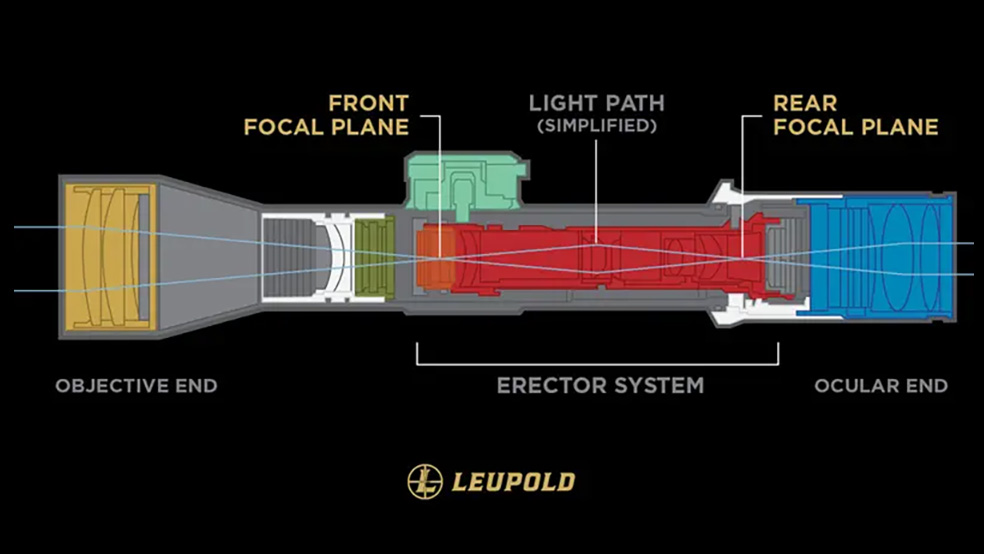

A riflescope can be thought of as a metal tube with a horizontal stack of optical glass inside. The job of this glass it is to grab ambient light and amplify it into the shooter’s pupil. This “bending of light” by the different pieces of glass inside the metal tube makes it easier for a rifle shooter to see distant targets. Without a viable aiming reference point, however, this metal tube would be worthless. For the reticle to work properly, it must be etched onto a piece of glass that is inside this stack of glass. Not only that, but this etched piece of glass may only sit in front or behind the erector tube (another sub-assembly inside the metal tube that is responsible for shifting the aiming point vertically and horizontally). The final positioning of the etched piece of glass results in important nuances and practical considerations for a shooter.

A first focal plane reticle with no magnification. Note the size of the reticle inside the scope.

First-Focal-Plane Reticles

First-focal-plane reticles sit in front of the erector tube assembly that is inside the scope. From the shooter’s perspective, a first-focal-plane reticle is most easily identified in that it either shrinks or grows depending on the level of magnification to which the scope is set. First-focal-plane reticles appear largest when the magnification level is highest, and they all but disappear when the zoom level is adjusted to the lowest setting. The most important thing about first-focal-plane reticles is that their hash marks remain calibrated for holds and shooting adjustments regardless of how large or small the reticle appears to the shooter. This means that you can also use those hash marks to estimate the distance to your target at any magnification, using formulas for either MOA or MRAD reticles.

Typically, this style of reticle is included in scopes meant for precision shooting at longer distances, where rifle shooters may encounter different targets at different distances and where the constant on-the-fly adjustment of ballistic firing solutions happen due to bullet drop and wind calls. Therefore, having the aiming system and its calibrations remain consistent becomes extremely practical. The Nightforce SHV 4-14×50 F1 recently reviewed is a great example of a first-focal-plane riflescope that fits the above criteria.

A first focal plane reticle at maximum magnification.

Second Focal Plane Reticles

As the name implies, second-focal-plane scopes place the reticle behind the erector tube assembly, the only other available location within the horizontal glass stack. This location means that from the shooter’s perspective, the reticle remains the same visual size regardless of magnification. Whether zoomed fully in or out, the sight picture will always looks the same in a second-focal-plane scope. In the case of reticles with specialized MOA or MRAD hashes and additional reference points, these typically only subtend correctly when the scope’s zoom level is fully adjusted. When adjusted to a lower magnification, only the central aiming point provides accurate distance-measuring information.

Is One Better Than the Other?

Historically, first-focal-plane riflescopes have always been more labor-intensive to manufacture as they require more sophisticated manufacturing techniques. Otherwise, any errors or defects in the glass will expand and become noticeable any time the scope’s zoom level is increased. This isn’t the case for second-focal-plane models, so they’re generally less expensive. However, whether a scope uses a first- or second-focal plane does not render a scope “cheap” or low-quality, so it’s not that one is better than the other.

Plenty of high-end scope manufacturers offer second-focal-plane models, especially for purpose-driven rifle shooting at targets of known size and distance where the shooter doesn’t need to “guess” and make ballistic estimates on-the-fly. Similarly, most hunting rifles use second-focal-plane reticles because hunters typically zero their rifle for point-blank range (using the same point of aim to land shots inside a certain diameter up to a limiting distance). Most hunting scenarios occur at short or intermediate distances, so dialing isn’t a concern either. Finally, because second-focal-plane reticles appear thicker on lower magnifications, they can be easier to see when juxtaposed against dense foliage. LPVOs on modern defensive carbines are mostly built with second-focal-plane reticles for much the same reason. Carbine shooters typically zero their glass to a certain distance that takes advantage of the cartridge’s ballistic trajectory. Once dialed in, LPVO (low power variable optic) shooters don’t really worry much about dialing either. And just like the hunter glassing in thick vegetation, it’s imperative that a carbine shooter can see their reticle at the lowest power. In fact, a drawback of first-focal-plane LPVOs is that their reticles can be hard to see at 1X magnification.

On the other hand, the precision shooter is better off using a first-focal-plane reticle due to variability in their shooting and the need for consistency and repeatability to remain constant regardless of zoom adjustment. These types of scopes are typically 5- to 7-power on the low end, so a first-focal-plane reticle will not fade against the background as easily, either. The best way to approach choosing a first-focal-plane vs a second-focal-plane reticle is to first consider the goals. Is one hunting? Is one outfitting their defensive carbine, or are they getting ready for their first PRS match?

Read the full article here