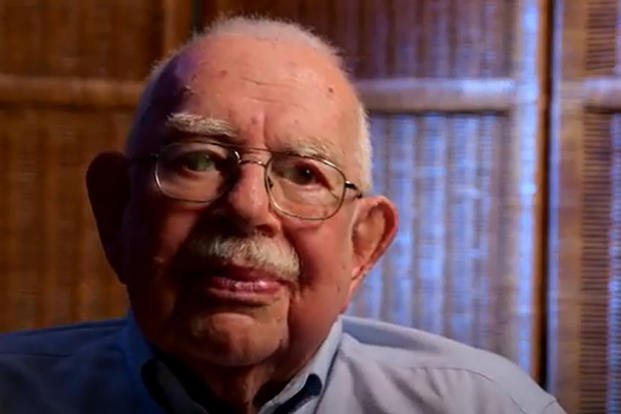

Escaping the festering hostilities in Germany against Jews in the 1930s, Rudy Pins kissed his father goodbye and boarded a train. Then 12 years old, Pins — bound for a new life in the United States — never saw his family again.

After the policy forbidding German Jews from serving in the U.S. military was changed during World War II, Pins joined the Army and was going through basic training, believing he would be sent overseas to battle the Nazis. The Army had other ideas, though.

“I was called back to headquarters, and a colonel there, he said, ‘I don’t know what this is all about, Private, but I have secret orders for you to take a bus to Alexandria, Virginia. Go to the post office and call this telephone number,'” Pins told the American Heroes Channel.

With his German roots and knowledge of the language, Pins was a perfect candidate for a military intelligence program at Fort Hunt — a sprawling, former Civilian Conversation Corps camp within driving distance of the Pentagon — where German POWs were interrogated to glean information that would be beneficial to the Allieds’ mission. As the war was concluding and in its aftermath, German scientists were debriefed there as well, with some of their information proving priceless during the Cold War; one of them, Wernher von Braun, later emerged as a leading figure in NASA’s space program.

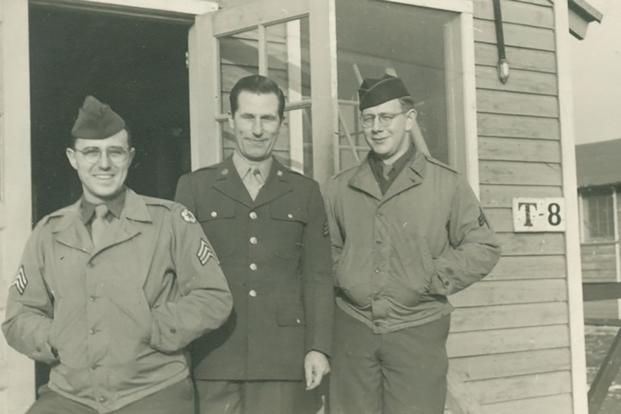

The goings-on at Fort Hunt were so secret that they were known only by the facility’s mailing address: P.O. Box 1142. From 1943 through 1946, more than 3,400 prisoners (including 15 Nazi generals) were processed at Fort Hunt, according to Robert K. Sutton’s 2022 book, “Nazis on the Potomac: The Top-Secret Intelligence Operation that Helped Win World War II.” Army personnel officially were trained in the art of interrogation at the Camp Ritchie Military Intelligence Training Center in Maryland before they were transferred to Fort Hunt with orders to tell absolutely no one, including family, about their activities. Like Pins, several interrogators were Jewish immigrants fleeing Nazi oppression, “incredibly smart individuals who were recruited here and very passionate about winning the war,” according to the National Park Service.

While the Army’s Military Intelligence Service spearheaded the program, officials with the Navy’s Office of Naval Intelligence interviewed the POWs, too. The prisoners were never physically harmed, Pins told CBS in 2014.

“You don’t get people to talk by beating them or waterboarding or anything of that nature,” Pins said. “If you make life for certain prisoners fairly easy, they will relax.”

Make no mistake: This installation of nearly 90 barracks and other facilities was no Club Med. Trained in the delicate art of persuasion, the interrogators were not above using psychological means to coerce uncooperating prisoners. Some were threatened with being handed over to the Russians, considered by many POWs to be a much more menacing proposition than being captured by the Americans, if they didn’t talk.

By whatever means — the military also employed listening devices and stool pigeons — the program was certainly prolific, producing more than 5,000 reports that were forwarded along to the Army, Army Air Force or Navy.

“It could be information about a target for the Air Force to bomb,” Pins said, per the American Heroes Channel. “It could be information about some individual in Germany, political. It could be information about the mood or the morale of the German people.”

From the POWs, the interrogators learned where Germans were primarily producing V-1 and V-2 rockets and bombed the facility. They unearthed details not only about weapons technology but also military operations, and they discovered that Germany intended to send a submarine to the Pacific theater to assist Japan. That plan was thwarted when the sub, U-234, surrendered in the North Atlantic in May 1945 with two disassembled jet fighters and enough uranium to construct eight atomic bombs onboard.

Besides the interrogators, the Army ran a robust escape and evasion (E&E) program and a military intelligence research department at Fort Hunt, as well as a mission that ultimately would bring about 1,600 prized German scientists here.

Fort Hunt was returned to the National Park Service in January 1948, and in his book, “Nazis of the Potomac,” Sutton said the first public realization of the happenings there came in 1990 when a former soldier published his memoir. Even 4½ decades later, the U.S. military went to such great lengths to keep the program secret that it bought as many copies of the book as possible.

The files were finally declassified later in the 1990s, several years before the National Park Service started the Fort Hunt Park Oral History Project. In 2007, some surviving service members assigned to P.O. Box 1142, including Pins, reunited. During that gathering, Pins was asked how much of the intelligence they obtained contributed to the Nazis’ demise.

“I would hope so, but, you know, it’s like a jigsaw puzzle,” said Pins, who died in 2016 at the age of 95. “You need all the pieces to get the picture, and we got some of the pieces.”

Want to Know More About the Military?

Be sure to get the latest news about the U.S. military, as well as critical info about how to join and all the benefits of service. Subscribe to Military.com and receive customized updates delivered straight to your inbox.

Story Continues

Read the full article here