Book review writer Richard Sisk on “Grant’s Enforcer” by Guy Gugliotta, Vietnam-era Navy swiftboat veteran and award-winning former reporter for The Washington Post, the Miami Herald and United Press International.

President Ulysses S. Grant had put the night riders of the Ku Klux Klan on notice that he was ready to use the full powers of his office to break their white terrorist grip on the states of the former Confederacy. But he needed to pick an enforcer to break the Klan’s hold on the South.

Grant’s Groundwork

Grant already had the legal and legislative tools at his disposal for the job. In May 1870, Congress had approved the Civil Rights Act, also known as the First Enforcement Act, which was aimed right at the hooded thugs of the KKK. The law made it a felony with up to $5,000 in fines and up to 10 years in jail for two or more people to “band or conspire together, or go in disguise upon the public highway or upon the premises of another, with the intent to violate the civil rights of any citizen.”

Read Next: Trinity Test Fallout Victims in New Mexico Finally Get Compensation After 80 Years

In a later proclamation, Grant called on the people of the South to reject the KKK and recognize the rights of former slaves “through their own voluntary efforts.” But if that failed, he said, he would “not hesitate to exhaust the powers thus vested in the Executive, whenever and wherever it shall become necessary” to keep the peace and guarantee equal protection of the laws for former slaves.

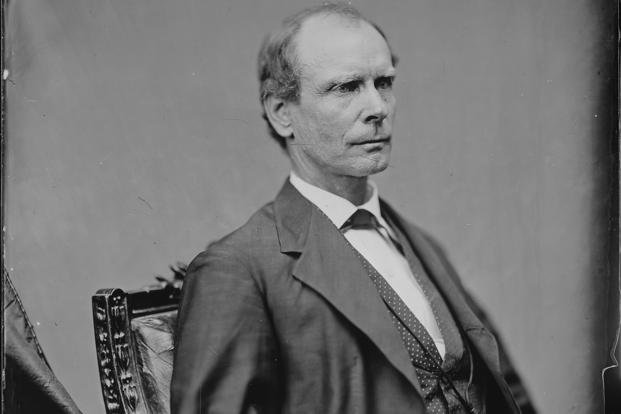

Amos T. Akerman, Grant’s Enforcer

Grant needed an attorney general to turn the newly enacted 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments on citizenship, the right to vote and entitlement to due process of law for “freedmen” into courtroom weapons that would decimate the “Lost Cause” imaginings of the Klan.

To do that, Grant made the unlikeliest choice of Amos T. Akerman, a minor postwar official in Georgia, to become the top law enforcement officer in the land.

Akerman was a curious case, as depicted in Guy Gugliotta’s exhaustively researched new book on what amounted to the twilight of the Reconstruction era, “Grant’s Enforcer: Taking Down the Klan.” In the book, Gugliotta draws heavily on firsthand accounts of Klan members and their victims taken from diaries, newspaper accounts, court records and congressional testimony to turn what could have been a dry procedural into a historical page-turner with the riveting impact of a novel.

Akerman, the ninth of 12 children, was born in New Hampshire and was an 1842 graduate of Dartmouth College. He moved south and read for the law, became a slave owner and enlisted in the Georgia militia in 1863 but never saw action.

His obscurity was probably a factor in his favor in the cutthroat politics of the era in Washington, D.C, where the Southern Bloc of Democrats saw political power emanating from white supremacy and the planter class while the Republicans, at least initially, looked to protect the rights of four million newly freed Black men and women.

So why did Grant pick this virtual unknown?

“Eventually, the theory arose that Akerman, rather than having been selected in spite of being a Southerner, had instead been appointed because he was a Southerner,” Gugliotta wrote. “The Civil War had been over for five years. And Grant had decided that diversity was a good idea. It was time to bring the prodigals back into the fold.”

A Dangerous Job

Akerman would have little support from the military in going up against the Klan. After the defeat of the Confederates, the Army had a force of 250,000 occupation troops in the South, but that force had dwindled to 88,000 by the fall of 1865. By the time Akerman appeared before Congress in 1870, there were 22,000 federal troops in the South.

Akerman also knew well that he was taking on a dangerous job as attorney general, once it became known in Georgia that he was now a member of the hated “radical” Republican Party.

“On the road, innkeepers frequently refused him lodging and once, when they did not, Akerman checked out of his hotel only to find that his horse had been shaved and painted with black and white zebra stripes,” Gugliotta wrote. “That was not his horse, he said, and he refused to mount. Later, he learned that a gang of Ku Klux had planned to ambush and perhaps kill him. They had painted the horse so they could identify him as he rode out of town.”

Grant’s thinking on his choice of Akerman as the only Southerner in his cabinet is still something of a puzzle, but in 1870, “Klan terrorism was on a massive upswing, and Grant was losing patience,” Gugliotta wrote. “He understood violence as well as anyone then living, and when he named Akerman as his attorney general he picked a man who had as much or more experience with white terrorism as anyone he might have chosen. Whether he knew it or not, Grant had found his enforcer.”

Justice for Jim Williams

Akerman decided to go after the Klan first in South Carolina, particularly in York County. He thought if he could beat the night riders there, he could use the same types of prosecution and courtroom tactics in other southern states.

One of the most consequential cases Akerman oversaw was a case against Klan leaders who lynched black militia leader Jim Williams in York County in March 1871. Gugliotta’s chilling account of Williams’ death, gleaned from newspaper accounts, diaries, and court and congressional records, and the heartbreaking testimony of his wife afterward serve to underscore the fundamental and deranged villainy of the Klan.

“Jim Williams and his wife Rose heard the Klan coming through the woods around 2 a.m.,” Gugliotta wrote. “Williams had enough time to dash outside and duck beneath the house.” Rose Williams said later that maybe nine or 10 Klansmen had barged through the front door: “I was scared because I thought they was going to kill me too.”

The Klansmen tore up the floorboards to find Williams. “We hauled him out and placed a rope around his neck and started back toward our horses,” Klansman Milus Smith Carroll recalled, and then “someone spied a large tree with limbs running out, 10 or 12 feet from the ground, and suggested that was the place to finish the job.”

Williams grabbed at a branch to break his fall until one of the Klansmen hacked at his hand with a knife to force him to let go. “He died cursing, pleading and praying all in one breath,” Carroll said.

Rose Williams would testify at the trial of her husband’s killers under questioning from David T. Corbin, one of Akerman’s prosecutors. She described how she peeked through the window when the Klansmen dragged her husband from the house while she waited, terrified, with her children before going out at around noon the following day. Gugliotta’s book captures the chilling exchange.

Lasting Impact

By the time he left office in December 1871, Akerman had overseen more than 1,100 prosecutions, according to the National Park Service.

At a July 20 book signing in Washington, D.C., Gugliotta said that in some ways, Akerman’s methods endorsed by Grant could be seen as the beginnings of the civil rights movement in the U.S., although Akerman resigned after only 18 months in office and the North lost interest in imposing reform on the South, allowing the Jim Crow era of segregation and voter suppression to fill the void.

But Akerman’s actions against the Klan essentially put the night riders out of business as a significant presence in the South until after World War I, Gugliotta said.

Want to Know More About the Military?

Be sure to get the latest news about the U.S. military, as well as critical info about how to join and all the benefits of service. Subscribe to Military.com and receive customized updates delivered straight to your inbox.

Story Continues

Read the full article here