Some hunters want a dedicated rifle for every purpose. Others say they prefer a single gun that can do just about anything. Most of us land somewhere in the middle, but Remington was aiming for the one-gun crowd when it released the .22 Accelerator in 1977.

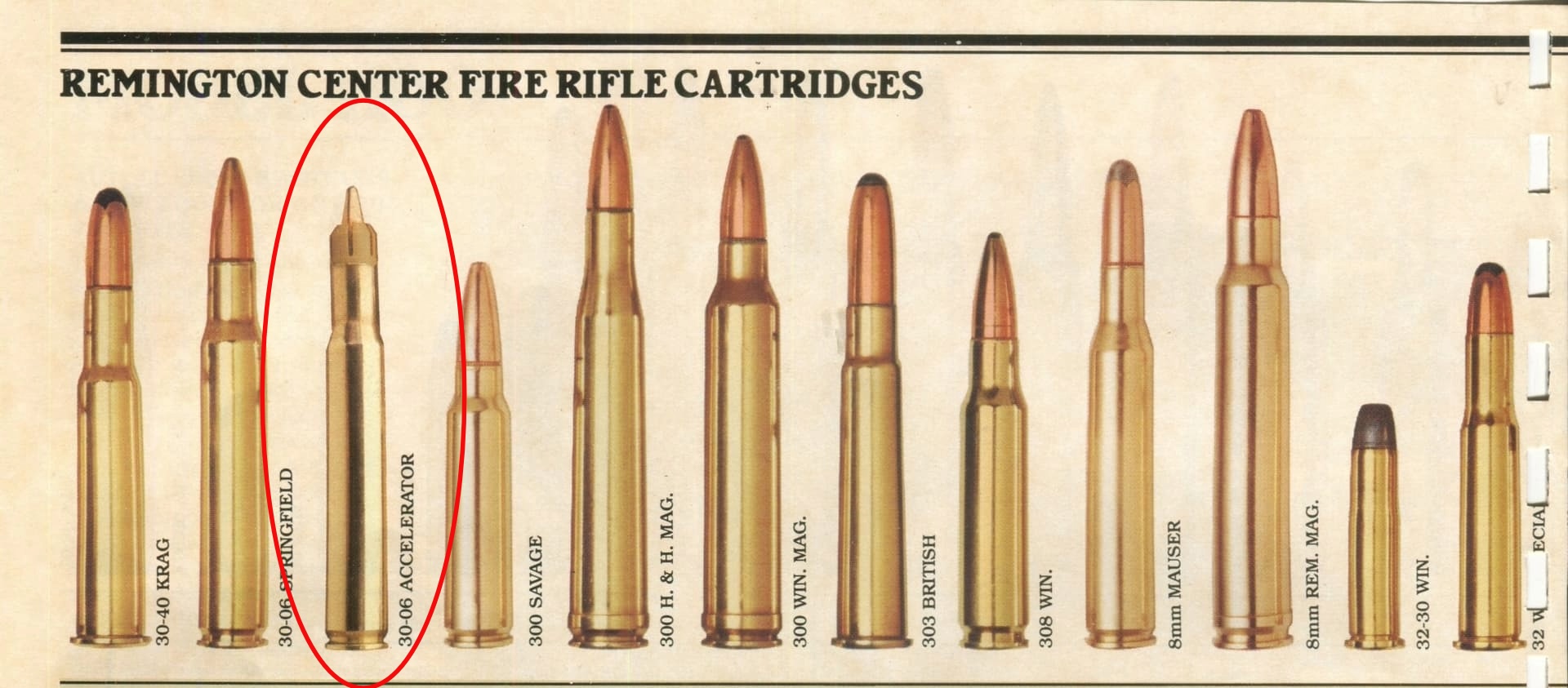

The .22 Accelerator stuffed a 55-grain, .224-caliber soft-point bullet into a .30-06 Springfield cartridge. But it didn’t adjust the neck size of the aught-six. Instead, it fitted the bullet into a 7-grain, six-fingered, plastic sabot and then loaded that bullet and sabot into a standard .30-06 case.

This design allowed the user to fire super-fast, .22-caliber pills from the .30-06 rifle they already owned. With the release of .30-30 and .308 Win. versions in subsequent years, the .22 Accelerator gave hunters the ability to chase everything from moose to prairie dogs with a single rifle.

“Now your 30-30 deer gun can double as a varmint gun. With the ballistics of a .222 Rem.,” reads a 1979 Remington catalogue. “For only pennies more per cartridge, you can broaden your rifle’s game-getting potential. And your hunting or target shooting enjoyment.”

How Did It Work?

Sabots are a little like the wad used in a shotgun shell. But instead of cupping a charge of BBs, a rifle sabot cups a single projectile. Shotgun and muzzleloader hunters are probably more familiar with this concept than anyone else. Sabot rounds are one of the most common kinds of muzzleloader projectiles, and they can also be loaded in a shotgun shell and fired–accurately enough–through a rifled barrel.

The sabot, rather than the bullet, contacts the rifling and spins the projectile to achieve stability in flight. Upon exiting the barrel, the sabot in the Accelerator separates from the bullet about 14 inches from the muzzle and can be found 40 to 100 yards downrange, according to “Cartridges of the World.”

As you might expect, the Accelerator did indeed accelerate bullet velocities above and beyond the original cartridge. According to a 1979 Remington ammunition catalogue, the .30-06 Accelerator could push that 55-grain bullet a whopping 4,080 feet-per-second (fps). The .30-30 version clocked in at 3,400 fps, which is still faster than most .223 Remington loads using the same projectile.

Remington leadership understandably surmised that giving hunters the ability to turn their .30-30 into an effective varmint rifle would be an extremely attractive proposition. The company released several versions after the original .30-06, and the concept appeared destined for commercial success.

Not Well Enough

Alas, that was not the case. The Accelerator line suffered from several maladies that, as far as I can tell, limited its production run. It was introduced in 1977 and was still going strong in 1980, according to a catalogue from that year, which listed the .30-06 and .30-30 versions. The .30-30 was highlighted in that catalogue as “new for 1980,” so I assume it continued production for several years after that.

But it wasn’t destined for greatness. Accuracy was the most frequently cited problem with the Accelerator. Since the rifling interfaces with the sabot rather than the bullet, some users reported inconsistent bullet rotation. This could sometimes cause the bullet to wobble or tumble mid-flight, which is never a recipe for consistent groupings.

Not everyone reported accuracy issues. In fact, Frank Barnes’ experience was that the Accelerator rounds wouldn’t shoot much worse than a standard cartridge out of the same gun.

“The Accelerator cartridges appear to group about the same as the standard .30-caliber cartridge does in the same rifle. This is just what the factory says it will do. In other words, if your rifle ordinarily makes 3-inch five-shot groups at 100 yards, it isn’t going to do any better with the Accelerator,” writes the author in “Cartridges of the World.”

This was fine for taking coyotes at 75 yards, but became more of a problem targeting prairie dogs at 300. While the “varmint rifle” concept is fluid, hunters are usually looking for something that shoots small bullets quickly and accurately. The Accelerator checked the first box but sometimes struggled with the second. A rifle that shoots three-inch groups at 100 yards probably won’t be making many shots on a squirrel-sized critter at distances much beyond that.

Rifle shooters also weren’t fans of the plastic fouling left behind by the sabots. Plastic, being much softer than steel, doesn’t damage the barrel by itself. But some worried that plastic fouling could trap moisture, which might lead to corrosion.

I’m not sure whether this concern had any real merit. But if you were already on the fence about the Accelerator, learning about a new material to clean out of the bore gave hunters another reason to give Remington’s new rounds a pass.

Some have also claimed that the government and anti-gun activists forced Remington to halt production due to fears about the bullets being untraceable. Since the sabot contacted the rifling and not the bullet, the theory went, forensic ballisticians would be unable to study rifling marks and determine which rifle a bullet came from.

While I haven’t been able to find any evidence to back this up, it sounds like the kind of argument the gun control lobby would have made. After all, they tried to convince lawmakers in the 1980s that “plastic guns” like Glocks should be banned because they were invisible to metal detectors (they weren’t). Calling the Accelerators an “assassin’s bullet,” as I’ve seen claimed, seems right in line with that tactic.

Where Are They Now?

Still, I don’t think Remington stopped production due to pressure from the government. More likely, they stopped production because the Accelerators were questionably accurate and didn’t fill a real need. A dedicated .223 Rem. or .22-250 rifle is much more effective, and a reloader can work up a pretty good varmint load using lightweight .30-caliber bullets.

That being said, if you’re intrigued by the idea, you can still get your hands on old boxes of Accelerator cartridges. Websites like GunBroker usually have some for sale, though you’ll pay between $40-$80 for a box of 20.

You can also roll your own. You can purchase the sabots by themselves, and with a bullet seater and case neck expander, you’ll be well on your way to creating your own .22 Accelerator cartridges.

And who knows? Depending on your proficiency at the reloading bench, you could solve some of Remington’s accuracy issues and create a real big-game/varmint do-it-all rifle.

Read the full article here