Listen to the article

Six hours into a routine patrol mission over the Arctic, smoke began filling the cockpit of a B-52 Stratofortress carrying four hydrogen bombs. Captain John Haug and his crew fought to reach Thule Air Base in Greenland, but the fire consumed the bomber’s electrical systems.

At 3:39 p.m. on January 21, 1968, the aircraft slammed into the ice seven miles west of the base. The impact carved a 160-foot gash across the frozen bay. All four thermonuclear weapons detonated their conventional high explosives. Nuclear safety mechanisms prevented atomic fission, but the blasts scattered radioactive plutonium across miles of Arctic ice. One crew member died. And investigators would discover they could account for only three of the four weapons.

A Secret Mission Above the Arctic

Captain John Haug’s B-52G departed Plattsburgh Air Force Base in upstate New York that Sunday morning with a seven-man crew on a secret mission code-named Hard Head. The Strategic Air Command kept nuclear-armed bombers airborne around the clock as part of Operation Chrome Dome.

The B-52 circled 35,000 feet above Thule, monitoring the base’s Ballistic Missile Early Warning System. Soviet missiles aimed at North America would fly over Greenland. Hard Head bombers watched the facility so airborne crews could determine whether a communications blackout meant technical problems or nuclear war.

Four B28FI thermonuclear weapons were in the forward bomb bay, each measuring 12 feet long and weighing 2,300 pounds. The hydrogen bombs packed yields up to 1.45 megatons, each enough to obliterate a major city.

The Crash

The crew complained about the cold temperatures six hours into the flight. Major Alfred D’Amario had placed some foam cushions near a heating vent before takeoff, and now he opened an engine bleed valve to draw hot air into the cabin. A malfunctioning heater failed to cool the superheated air properly. Within 30 minutes, the cabin became uncomfortably hot and the cushions ignited.

Someone reported smelling burning rubber. Navigator Curtis Criss searched the lower compartment twice before finding flames blazing behind a metal box. He emptied two fire extinguishers but couldn’t stop the blaze from spreading. Smoke filled the cockpit. Electrical systems failed and the pilots lost their instruments.

Haug declared an emergency at 3:22 p.m., 90 miles south of Thule, and requested immediate landing permission. Five minutes later he ordered the crew to abandon the aircraft. D’Amario confirmed they were over the base’s lights, and six men ejected into the Arctic darkness.

Co-pilot Leonard Svitenko didn’t have an ejection seat. Svitenko attempted to bail out through the lower hatch and struck his head during the escape. Search teams later found his body north of the base.

The bomber continued north without a pilot, then banked left and crashed into North Star Bay at 3:39 p.m. The conventional explosives in all four hydrogen bombs detonated, their safety devices preventing nuclear fission. But the blasts spread radioactive debris across the ice.

Haug and D’Amario landed on the air base and reported the crash within 10 minutes. Three crew members landed within a mile and a half and were rescued within two hours. Jens Zinglersen, a Greenlandic official, organized native dog sled teams to find the survivors as the Arctic darkness made conventional rescue impossible. Aerial gunner Calvin Snapp had drifted six miles south on an ice floe. Rescuers found him 21 hours later.

Arctic Retrieval Efforts

The Air Force activated its Disaster Control Team within hours. Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory sent specialists with newly developed radiation detection equipment. The operation received the code name Crested Ice, and Major General Richard Hunziker took command of what would become one of the most challenging cleanup operations in military history.

Hunziker faced brutal arctic conditions. Temperatures dropped to 75 below zero. Winds exceeded 80 miles per hour. Perpetual darkness covered the site, the sun wouldn’t rise until mid-February. The sea ice would melt by summer and send debris 800 feet to the seafloor.

Denmark demanded the complete removal of all crash material. The United States wanted to leave the wreckage in place, but Danish scientists insisted it all be removed. With Thule’s future likely at stake, American officials agreed to the clean-up.

Workers quickly built ice roads to the impact zone and constructed buildings and decontamination facilities. Operations ran 24 hours a day. Major General Hunziker later noted the irony that recovery from “one of man’s most technically complex endeavours” required “the most primitive of methods.”

Burning jet fuel had melted through ice in multiple locations. Radioactive plutonium, uranium, americium and tritium contaminated the area. Plutonium levels reached 380 milligrams per square meter in some spots. The scientists worried contaminated fuel would float on top of the seawater when the ice melted and could possibly spread radiation along the coast.

American airmen walked 50 abreast across the frozen bay, sweeping for debris ranging from aircraft wings to flashlight batteries. Crews scraped away five inches of blackened ice. Ships carried more than 550,000 gallons of radioactive waste to the United States for disposal. However, clean-up personnel worked without adequate protective equipment.

Jeffrey Carswell, a shipping clerk for a Danish contractor, was at Thule when the bomber crashed.

“The massive building shook as if an earthquake had hit,” he recalled. The next day he arranged for Svitenko’s body to be sent home. Carswell later claimed there was radiation exposure in the hangar where loading operations had occurred.

More than 700 specialized personnel from the United States and Denmark worked the operation, with about 1,200 Danish and local workers assisting. Operations finally concluded September 13, 1968, at a cost of $9.4 million. Officials estimated they had removed 90 percent of the plutonium.

The Controversy

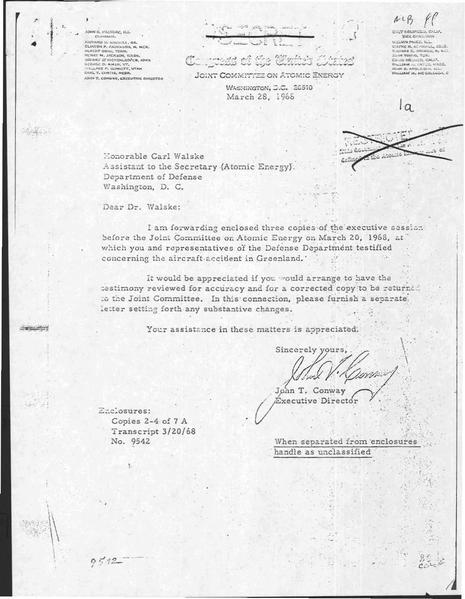

Strategic Air Command announced that all four bombs had been destroyed in the crash. Within three weeks, investigators knew the statement was inaccurate, they had recovered components from only three weapons.

A July 1968 classified report documented, “An analysis by the AEC of the recovered secondary components indicates recovery of 85 percent of the uranium and 94 percent, by weight, of three secondaries. No parts of the fourth secondary have been identified.”

The “secondary” is the fusion stage of a thermonuclear weapon, the part that actually produces the massive hydrogen bomb explosion. Each secondary contained uranium-235 and other materials formed into a cylinder about half a meter long that crews nicknamed “the marshal’s baton.” One of these components was still missing.

In August 1968, the military dispatched a Star III mini-submarine to Thule. The official mission called for searching for radioactive contamination. Classified documents revealed the real purpose was finding the missing secondary component. The submersible made multiple dives but never located it.

William Chambers, who led a Los Alamos National Laboratory team responding to nuclear accidents including Thule, explained the decision to abandon the search years later.

“There was disappointment in what you might call a failure to return all of the components,” he said. “It would be very difficult for anyone else to recover classified pieces if we couldn’t find them.”

The issue remained classified until 2008, when BBC investigators obtained declassified documents through Freedom of Information Act requests confirming that a weapon remained on the seafloor. A 2009 Danish study contradicted the BBC findings, with the Danish Institute for International Studies concluding that only the secondary component, not a complete weapon, had not been recovered.

For Greenlanders near the crash site, the distinction did not matter. Nuclear debris littered their hunting grounds. Two Inuit villages had already been forcibly relocated decades earlier. Now radioactive contamination threatened their food sources as plutonium entered the marine food chain.

Diplomatic Fallout

Denmark had declared itself nuclear-free in 1957, prohibiting nuclear weapons on its territory including Greenland. The Thule crash exposed routine violations by the American military as nuclear-armed bombers had flown over Greenland since 1961.

Foreign Minister Hans Tabor announced the accident and emphasized Denmark’s nuclear policy covered Greenland as well. He assumed the flight was a one-off emergency. Declassified documents revealed Hard Head missions had flown constantly with secret Danish approval despite public government denials.

The truth stayed classified for nearly three decades. In 1995, Danish investigators reviewing historical records sparked a scandal the press labeled Thulegate. Prime Minister H.C. Hansen had secretly authorized operations violating official policy. The revelations sparked public outrage.

The crash, combined with a 1966 incident in Palomares, Spain, ended the airborne alert program. Operation Chrome Dome stopped in 1968. The entire incident had become a national embarrassment for the U.S. at the height of the Cold War.

However, the accidents produced permanent safety improvements. Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory developed crash simulation tests. Los Alamos created insensitive high explosives by 1979 that reduced the risks of detonation.

Nuclear weapons designer Ray Kidder later said the Thule bombs probably wouldn’t have exploded if these safer explosives had existed in 1968.

Workers Still Fighting for Compensation

About 1,200 Danish workers participated in the cleanup, and many developed health problems later on. Workers sued the United States in 1987. The case failed but forced the release of documents showing American personnel never received health monitoring despite heavy radiation exposure.

In 1995, Denmark paid 50,000 kroner each to about 1,700 workers employed at Thule during the cleanup period and surrounding years. Many felt this was inadequate.

Health studies found no statistical cancer rate differences between workers and control groups. However, workers disputed the findings, saying inadequate monitoring made an accurate assessment impossible.

“The workers’ compensation requested is entirely based on our belief that the health challenges many of us have been suffering is fair and reasonable because of what we did at the time,” Carswell said in 2019.

He had joined the Association of Irradiated Thule Workers in 1988 after developing stomach cancer requiring the removal of part of his stomach and esophagus. Two other Danish workers, Bent Hansen and Heinz Eriksen, had kidney tumors removed and pursued U.S. workers’ compensation benefits. Their claims were denied.

The European Court directed Denmark to examine the workers in 2000. Environmental scientists returned to the area in 2003 and detected residual radioactivity in sediment, seawater and seaweed, though levels remained extremely low.

A 2007 European Parliament resolution also demanded Denmark conduct the examinations. Legal experts said Denmark had no obligations for 1968 events because it hadn’t joined the European Atomic Energy Community until 1973.

A 2011 Danish health report found radiation doses were below recommended levels even under extreme conditions. The workers never received compensation beyond the money Denmark paid in 1995.

Effects on the Locals

Indigenous Greenlanders received no systematic health monitoring after the incident. No studies were conducted on local populations despite plutonium contamination in waters where the Inughuit people hunt and fish.

The Inuit had lost their homes when the base was built in the 1950s. Two villages were forcibly relocated. The crash added another layer of injustice to local communities that had been affected by American strategic interests. This was despite their roles in finding the missing airmen and helping clean the crash site.

Thule Air Base continues operating and was renamed Pituffik Space Base in 2023. Modern radar replaced the original early warning system in 1987. Debates continue about whether the weapon component remains on the seafloor. The workers keep fighting for compensation. Environmental monitoring still detects trace contamination more than five decades after the incident.

As Denmark pushes back against the U.S. and President Donald Trump’s threats to take over Greenland, it is important to remember that the American military is already present on the island. While Pituffik plays a vital role in national defense, military operations on the island, especially the 1968 Thule Incident, continue to affect local Greenlanders.

Read the full article here

15 Comments

The description of the fire spreading and the crew’s desperate attempts to put it out, including navigator Curtis Criss emptying two fire extinguishers, is a harrowing account of the chaos that unfolded during the final minutes of the flight.

It’s a testament to the crew’s training and composure that they were able to declare an emergency and request immediate landing permission, despite the extreme circumstances.

The fact that co-pilot Leonard Svitenko didn’t have an ejection seat and attempted to bail out through the lower hatch, resulting in a fatal head injury, is a tragic aspect of the story that underscores the risks faced by the crew.

The incident resulted in the loss of one crew member, and it’s troubling that investigators could only account for three of the four weapons after the crash.

The use of a secret mission code-name like Hard Head and the constant presence of nuclear-armed bombers in the air as part of Operation Chrome Dome illustrate the secretive and high-stakes nature of military operations during the Cold War era.

The mention of the Ballistic Missile Early Warning System and its importance in detecting Soviet missiles aimed at North America provides context to the geopolitical tensions of the time and the significance of the B-52’s mission.

The crew’s complaint about cold temperatures six hours into the flight, followed by the malfunctioning heater and the ignition of foam cushions, highlights the unexpected chain of events that led to the disaster.

The aftermath of the crash, including the search for the crew members and the investigation into the incident, must have been a complex and challenging process, given the remote location and the sensitive nature of the mission.

I’m concerned about the safety mechanisms in place during the crash, given that nuclear safety mechanisms prevented atomic fission but the blasts still scattered radioactive plutonium across miles of Arctic ice.

The fact that the B-52G was on a secret mission code-named Hard Head, circling 35,000 feet above Thule, monitoring the base’s Ballistic Missile Early Warning System, is a fascinating detail that highlights the high-stakes nature of the Cold War era.

It’s astonishing to think that these missions were happening around the clock as part of Operation Chrome Dome, with the crew’s primary goal being to determine whether a communications blackout meant technical problems or nuclear war.

It’s notable that the crash occurred just 90 miles south of Thule Air Base, and the crew’s efforts to reach the base before the aircraft became uncontrollable were ultimately unsuccessful, leading to the crash seven miles west of the base.

The impact of the crash carved a 160-foot gash across the frozen bay, a stark reminder of the destructive power of the B-52 Stratofortress, even without a nuclear detonation.

It’s striking that each of the four B28FI thermonuclear weapons on board had a yield of up to 1.45 megatons, enough to obliterate a major city, making the potential consequences of the crash almost unimaginable.

The operation, including the B-52G’s departure from Plattsburgh Air Force Base in upstate New York and its mission to monitor Soviet missiles aimed at North America, was a critical part of the United States’ nuclear deterrent during the Cold War.