Listen to the article

Twenty-seven cavalrymen charged a group of Japanese infantry at Morong, Philippines, on January 16, 1942. They scattered a substantial force of enemy soldiers and then held their position for five hours. Only three men were wounded. It was not only a stunning success in a horrific battle, it was the last official mounted cavalry charge in U.S. Army history.

The charge happened four months after the Army decided horse cavalry was obsolete. Only weeks later, the regiment of cavalry troopers would be forced to kill their horses for food before finally surrendering to Japanese troops.

Mechanization Over Horses

The Army had spent the 1930s deciding whether to keep horse cavalry as the main mobile arm or convert to mechanized units. Budget constraints during those years meant the service couldn’t afford both. Tanks and trucks broke down frequently, consumed fuel, and cost significantly more than horses.

Orders went out in 1938 to motorize most remaining animal-drawn units. Nevertheless, many Army leaders were raised and trained in the field of cavalry, refusing to change the battle-tested doctrine.

Major General John K. Herr testified before Congress in 1939 that horse cavalry had “stood the acid test of war.” Tanks hadn’t proven themselves the same way, he argued.

By 1940, the service maintained just two horse cavalry divisions. However, most Army units maintained horses, pack-mules and other animals for supply, reconnaissance, or outright combat purposes. Independent cavalry regiments were spread across the nation, still prepared to conduct combat as they had for decades.

The Louisiana Maneuvers in September 1941 finally settled the debate. Around 34,000 horses and 50,000 wheeled and tracked vehicles deployed across 3,400 square miles of Louisiana for mock battles as the nation prepared for war. The first exercise had horses performing well against their notional enemies. The second exercise ended when General George Patton’s armored group encircled the entire opposing army three days ahead of schedule.

The maneuvers convinced Army leadership to fully embrace mechanization.

The 26th Cavalry in the Philippines was one of the few units to maintain its horse-driven organization. Distance and the Philippine Department’s administrative oversight left them mounted. They remained one of the Army’s only regiments still fighting on horseback when the U.S. entered WWII.

The Philippine Scouts

The Army organized the Philippine Scouts in 1901 to fight insurgents after the Spanish-American War. President Theodore Roosevelt officially incorporated them into the Regular Army that October with 5,000 men in 50 companies. Filipino enlisted men served under American officers.

The Scouts built a reputation over the next two decades. They helped capture revolutionary leader Emilio Aguinaldo in 1901. They suppressed Moro rebels in the southern islands. They garrisoned the Philippines when most U.S. troops deployed to Europe during World War I.

Congress approved their full induction into the Regular Army after that war. By 1922, the Scouts numbered 6,000 organized into formal regiments. The 45th and 57th Infantry. The 24th and 25th Field Artillery. The 91st and 92nd Coast Artillery. Supporting units included engineers, medical, quartermaster, and military police.

The 26th Cavalry Regiment formed in October 1922 from personnel of the 25th Field Artillery and 43rd Infantry, both Philippine Scout units. They inherited horses from the 9th Cavalry when that regiment transferred to Fort Riley, Kansas. The mounts were crossbreeds shipped from the United States.

Filipino enlisted men filled the ranks. American officers commanded them. Many noncommissioned officers had served more than 20 years in the service.

By late 1941, the 12,000-strong Philippine Scouts formed the backbone of American defenses in the islands. Survivors of Bataan later described them as the most professional, best-trained troops available.

Colonel Clinton Pierce commanded the 26th. With his dapper mustache, rugged features, and bulldog physique, Pierce embodied his generation of legendary cavalrymen. The Illinois native had served as a corporal in the National Guard during the 1916 Mexican border campaign. Commissioned in March 1917, he’d spent two decades in cavalry. He graduated from the Cavalry School advanced course in 1932. He took command of the regiment at Fort Stotsenburg in May 1940.

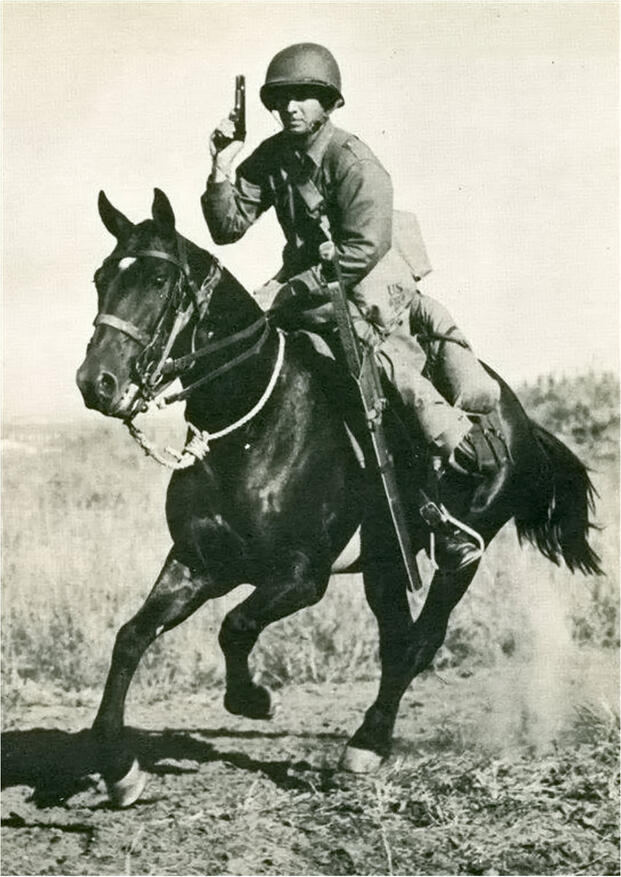

On November 30, 1941, the regiment had 787 enlisted men and 55 officers. In addition to mounted troops, they maintained a headquarters troop, a machine gun troop, and a platoon of six scout cars with trucks. The regiment was the first Filipino unit issued the new M1 Garand rifle. Mounted troops carried them in saddle scabbards.

The Japanese Invasion

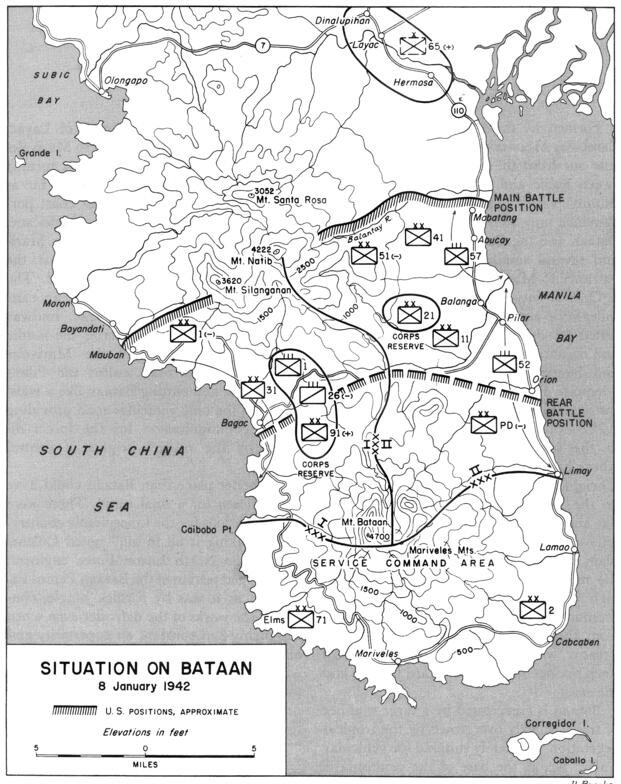

Japanese bombs hit Clark Field and other Philippine installations on December 8, 1941, hours after the Pearl Harbor attack. War Plan Orange-3 called for American and Filipino forces to withdraw to the Bataan Peninsula if overwhelmed. Defenders would hold the entrance to Manila Bay while the Navy fought across the Pacific to relieve them.

The plan estimated a six-month siege with supplies stockpiled for a garrison of 50,000. But General Douglas MacArthur had rejected the plan earlier in 1941 as too defensive. He’d spread supplies across the islands to support an aggressive strategy. When Japanese forces landed in overwhelming numbers, those dispersed caches became inaccessible.

MacArthur activated War Plan Orange on December 23. Some 90,000 troops and 26,000 civilians retreated into Bataan. Food supplies would last roughly two months instead of six.

Japanese forces under Lieutenant General Masaharu Homma landed at Lingayen Gulf on December 22. Four infantry regiments pushed south toward Manila. His 14th Army troops had fought in Manchuria and China. They outnumbered and outgunned the defenders.

During this assault, one of the only tank against tank battles occurred between U.S. and Japanese forces. Despite some successes, the American forces were gradually pushed further south.

The 26th Cavalry was given the mission of delaying the Japanese advance, even as tanks proved incapable of the job. They had to buy time for other units to withdraw to Bataan and establish better defensive positions.

General Jonathan Wainwright, commander of the North Luzon Force and a former cavalryman himself, later said Pierce’s unit were “the only ones to stop them from being in Manila in a few hours.”

Delaying Action

The regiment delayed four Japanese infantry regiments for six hours at Damortis during the initial landings. On December 24, they repulsed a tank assault at Binalonan. The cavalrymen used jungle terrain to separate tanks from infantry. They attacked individual vehicles from multiple directions with grenades and gasoline-filled bottles.

The fighting reduced the regiment from nearly 800 to 450 by December 24. Reinforcements brought strength back to 657 men. Through late December and early January, the 26th held the roadways to Bataan while other units prepared defensive lines.

Wainwright visited Pierce at his forward headquarters on the morning of December 24. The two old cavalrymen shared a bottle of scotch. Wainwright ordered the 26th to cover the withdrawal of his entire force.

Lieutenant Edwin Ramsey commanded a platoon in the regiment. The 24-year-old from Kansas had volunteered from the 11th Cavalry in California in June 1941. He had graduated from Oklahoma Military Academy where he played polo before receiving orders to the Philippines.

“I didn’t even know where it was, except that it was a warm country, it was tropical and they had a good polo team there,” Ramsey later recalled about volunteering for the Philippines.

The day before Pearl Harbor, Ramsey played in a polo match at Fort Stotsenburg. He was on the losing side. Wainwright was the umpire for the match. Twenty-four hours later, they were at war.

Ramsey and his troopers fought in each of these engagements as they were forced back by the superior Japanese force. His most famous action, however, would occur the following month.

The Charge at Morong

Wainwright wanted to anchor a defensive line at Morong on January 15, 1942. The coastal village sat strategically on Bataan’s west coast where the Batalan River formed a natural obstacle. Filipino troops from the 1st Division had tried to hold the position but withdrew. Wainwright needed an advance guard to scout ahead and hold the village until reinforcements arrived.

Ramsey’s platoon had just finished a reconnaissance mission. They were scheduled for rest. But Ramsey knew the terrain. He volunteered to go back out with his men.

Wainwright gave him direct orders on the morning of January 16. He was to take his men and ride to Morong, then hold it.

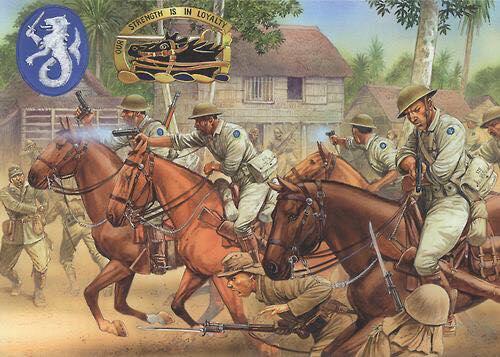

Ramsey assembled 27 mounted troops from different platoons. They rode north along the main road. When they reached the Batalan River at Morong’s eastern border, they swung west.

The village appeared deserted. Grass huts stood on stilts with livestock penned beneath. A Catholic church made of stone dominated the center. Ramsey halted his column and pulled out his binoculars. Three trails branched from the road. He signaled for his men to draw their Colt .45 pistols.

He divided the platoon into three squads and ordered a four-man point unit to advance. The point riders trotted into the village, pistols raised. Ramsey followed with the rest of the force.

Gunfire suddenly erupted from near the church. Private First Class Pedro Euperio took multiple rounds to his left arm and shoulder. He kept his pistol in his right hand while the reins dangled from his left elbow. The point unit wheeled and galloped back.

A Japanese advance guard had crossed the river and was moving through the village. Ramsey saw hundreds more enemy troops wading chest-deep across the river behind them. Some crossed along a bridge. His 27 men faced what appeared to be a battalion of enemy troops.

He had no time to establish defensive positions. They were already in the thick of it. The Japanese would overrun them in minutes.

Ramsey signaled his men into forager formation, a cavalry skirmish line where horsemen spread across a front with weapons ready. He raised his pistol and yelled “Charge!”

“Bent nearly prone across the horses’ necks, we flung ourselves at the Japanese advance, pistols firing full into their startled faces,” Ramsey wrote in his 1991 memoir. “A few returned our fire, but most fled in confusion, some wading back into the river, others running madly for the swamps. To them we must have seemed a vision from another century, wild-eyed horses pounding headlong; cheering, whooping men firing from the saddles.”

The mounted attack drove through the Japanese vanguard. The cavalrymen scattered the advance guard and took defensive positions in the village. For five hours, Ramsey’s force held Morong under heavy fire until reinforcements from Pierce’s main body arrived. The charge cost three men wounded. Amazingly, no one died.

Second Lieutenant Eliseo Malari from 2nd Platoon, Troop E, witnessed the attack. He later wrote that Ramsey “in leading his platoon into the battle fought like a hungry tiger.”

Wainwright awarded Ramsey the Silver Star for the action.

An Army on the Ropes

By early March, troop rations had run critically low. Animal food was gone. The horses were starving. Wainwright ordered all cavalry mounts slaughtered for food.

The general’s own prize jumper, Joseph Conrad, went first. Wainwright turned away with tears in his eyes after giving the order.

Ramsey learned about this happening to his chestnut gelding Bryn Awryn while recovering from a leg wound in a field hospital. The cavalrymen refused to eat meat from their mounts despite near-starvation.

“They shared all our dangers, loving and trusting us as we did with them,” one rider later said. “There’s a special bond, and we were the last to share it.”

The 26th converted to two squadrons after losing their horses. One became a motorized rifle unit. The other operated as a mechanized force with the remaining scout cars and a few British-made Bren carriers.

The Fall of Bataan

Bataan fell on April 9, 1942. Some 76,000 troops surrendered in the largest American surrender in history. Pierce, promoted to brigadier general and commanding the 71st Division, was among those captured along with Wainwright. At least 600 Americans and 5,000 Filipinos perished during the Bataan Death March to Camp O’Donnell.

Many more died during their imprisonment throughout the rest of the war. Pierce spent more than three years as a prisoner of war. He survived and was liberated in 1945.

Ramsey escaped into the hills of central Luzon. He joined Colonel Claude Thorpe’s guerrilla organization. Over three years, Ramsey helped command a force that grew to nearly 40,000 irregulars. They gathered intelligence for MacArthur’s return, sabotaged Japanese operations, and kept the resistance alive.

In June 1945, MacArthur personally awarded Ramsey the Distinguished Service Cross. The ordeal had cost him half his weight. He weighed 93 pounds when American forces liberated the Philippines in early 1945.

Legacy

The charge at Morong was the final official mounted charge conducted by an Army cavalry unit in U.S. Army history. American troops would ride into combat again in October of 2001, when Special Forces soldiers joined Northern Alliance fighters at the Battle of Cobaki in Afghanistan.

The same April when Bataan fell, the last horse-mounted cavalry unit in the continental United States turned in its animals in Nebraska. The Army maintains ceremonial horse units today for tradition and heritage. Modern cavalry units carry the name but operate tanks and helicopters instead. Pack animals continued to serve over the decades and are still used to a small extent by units in mountain terrain.

The 26th Cavalry Regiment received three Presidential Unit Citations and one Philippine Presidential Unit Citation. Individual awards included five Distinguished Service Crosses, 28 Silver Stars, and four Bronze Stars. The American Battle Monuments Commission lists 301 regiment members interred at Manila American Cemetery. The Fort Stotsenburg Cavalry Sculpture now stands in the Philippines, honoring the men who conducted the last official cavalry charge in U.S. history.

The regiment was inactivated in 1946 and disbanded in 1951.

Wainwright survived the rest of the war as a prisoner in a Japanese camp. He was present during the surrender ceremony on the USS Missouri in September of 1945. He summarized the regiment’s performance in an official report.

“I was personally present during a portion of this flight and cannot speak in too glowing terms of the gallantry and the intrepidity displayed by Colonel Pierce and all the officers and the men of the 26th Cavalry on this occasion.”

Pierce retired from the Army. He died in 1966. Ramsey left the Army in 1946 as a lieutenant colonel. He went on to a successful business career in Japan, Taiwan, and the Philippines. He died in Los Angeles on March 7, 2013, at age 95.

Read the full article here

6 Comments

I’ve been following this closely. Good to see the latest updates.

Solid analysis. Will be watching this space.

Great insights on Defense. Thanks for sharing!

Interesting update on The Last US Cavalry Charge in History: 27 Troopers Routed Japanese Forces in the Philippines During WWII. Looking forward to seeing how this develops.

This is very helpful information. Appreciate the detailed analysis.

Good point. Watching closely.