Listen to the article

Capt. Walter Fleming walked through the gap between two small Buddhist altars on a dirt road near Da Nang. One of his men followed a few steps behind. A mine detonated, wounding the sergeant and throwing him backward. Hours later, Fleming’s executive officer triggered another booby trap. Both times, Fleming stood within the lethal blast radius. Both times, he walked away uninjured.

He would survive 13 months of hellish combat in Vietnam while leading his Marines against a fierce and determined enemy. He would emerge without a scratch after facing countless close calls, the loss of his Marines, overwhelming enemy numbers, and the constant threat of death.

Joining the Marine Corps

Walter Fleming was born in Key West, Florida, in 1940. His father spent 24 years in the Coast Guard, including service during WWII, commanding search-and-rescue boats throughout Florida and the Caribbean.

At Florida State University, Fleming earned a business degree in 1962, but with the draft looming and the Vietnam War on the horizon, he joined the Marine Corps through the Platoon Leaders Class.

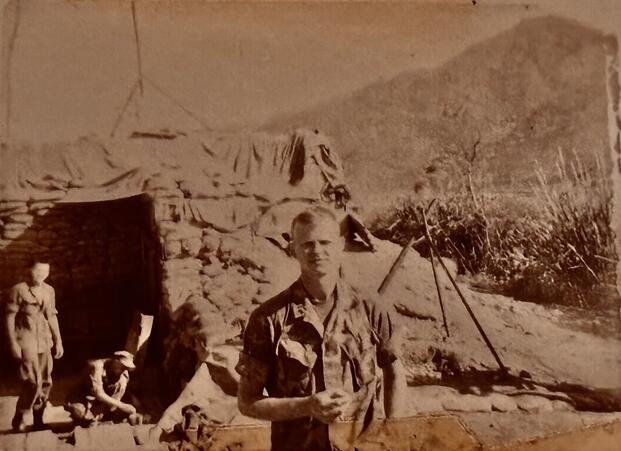

The brutal training that summer at Quantico under demanding sergeant instructors tested every candidate. Fleming commissioned in January 1963 as an infantry officer. For four years, he served with 2nd Battalion, 8th Marines at Camp Lejeune, commanding an 81mm mortar platoon on deployments to the Caribbean and Mediterranean.

On one amphibious assault exercise off the coast of Spain, Fleming witnessed two Marine helicopters collide mid-air, killing several Marines. He noted it was the first time he realized how dangerous the military could be.

By 1967, all his friends were deploying to Vietnam while Fleming remained aboard a naval ship as a Combat Cargo Officer. When the Tet Offensive erupted in January 1968 and the Marine Corps desperately needed officers, he finally got orders.

“I was apprehensive. You don’t know what to expect,” he said. “There’s a fear of the unknown.”

Arriving in Country

The moment Fleming’s plane touched down in Vietnam in February 1968, something felt fundamentally wrong. Officers and enlisted Marines crammed together in the reception building at the airfield without any separation, organization or guidance. It was chaos.

After one night, a truck delivered Fleming to a camp outside Phu Bai as it sustained artillery fire. He was assigned to 2nd Battalion, 27th Marines, a regiment hastily reactivated at Camp Pendleton and rushed to Vietnam. Initially designated as assistant operations officer, Fleming soon found himself commanding Echo Company.

The 27th Marines had the critical mission of patrolling the “rocket belt” around Da Nang Air Base, methodically covering every grid square to prevent North Vietnamese and Viet Cong forces from establishing firing positions within range of the installation.

The First Week

Within seven days of taking command in late February 1968, Fleming faced a loss that would haunt him for the rest of his life.

The company policy required two Marines to guard a wooden bridge on the main service road into the regimental combat base every night. On the other side sat a Vietnamese village. Fleming continued the procedure the previous commander set, sending two Marines with a radio each night to guard it.

One night in early March, the Viet Cong attacked the village. The two Marines positioned themselves in the culvert beneath the bridge for cover. The VC came with satchel charges.

They lobbed one directly under the bridge. The detonation killed both Marines.

“Everybody was upset about that; they were popular,” Fleming said. “I felt really terrible about it. How the hell could this happen? I felt so guilty.”

Fleming noted he still thinks about that night.

“But you gotta move on,” he said.

Facing the Communist Enemy

Through March and April 1968, Echo Company operated against two very different enemies.

The Viet Cong were local guerrillas, often indistinguishable from civilians, who used terror tactics and hit-and-run attacks. Fleming’s Marines never engaged them in stand-up fights.

“We had no respect for the VC whatsoever,” Fleming said. “Murderers that slip up and do horrible things. The VC were like the mafia in my book. They just intimidated everybody.”

The North Vietnamese Army, on the other hand were a formidable force.

“The NVA, I thought, were pretty darn good. They really had a purpose for fighting, as far as I could tell, freedom for their country. They were well-trained, well-equipped, equally armed with SKS and AK-47s for close combat,” he said. “I was a professional Marine. I viewed them as professional, too.”

The daily reality turned into grinding attrition. Mines and booby traps killed or wounded Marines almost every day. From his observation post, Fleming could watch as convoy trucks exploded on a regular basis after triggering mines.

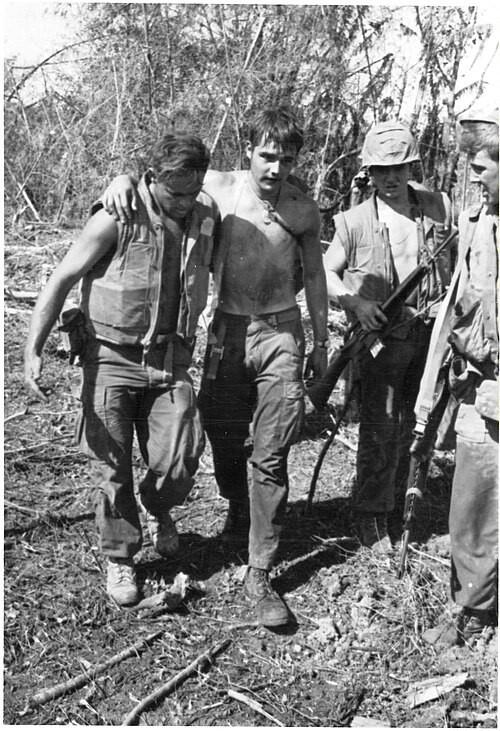

One afternoon in March, Fleming sent out a squad-sized patrol of six to eight Marines. They were ambushed by the VC in a village. Every Marine went down except one corporal, who got on the radio pleading for help.

“He was talking to me on the radio, asking, ‘What do I do? How do I get out?” Fleming recalled. “I said hold what you got, take it easy, let’s get some artillery in there and get these people off you. I was trying to find where he was.”

Fleming called in fire missions while a reactionary platoon ran toward the sound of gunfire.

The corporal kept talking, “They’re getting closer, skipper, they’re getting closer.”

The platoon arrived too late. The VC had killed him.

“That was heartbreaking,” Fleming said. “I was with him on that radio the whole time. That caused some heartache because of the way it happened.”

During a sweep near Da Nang a few days later, Fleming was moving down a dirt road when his unit reached an intersection where the Vietnamese had erected small Buddhist altars, little pagoda-like structures about three feet tall with barely enough space between them for a man to pass. Fleming walked right through the gap.

His weapons platoon sergeant followed seconds behind. A sudden blast threw the sergeant backward. A mine had detonated the moment he stepped through the gap. He was extracted from the field. Fleming never saw him again.

Only hours later, the company moved to establish a new position. Fleming and his executive officer moved forward to scout the area. As soon as the XO reached the position, another booby trap exploded.

“He got injured and I didn’t even get hit at all,” Fleming said. “I was in the lethal area with him, and nothing happened.”

Taking the Bridge

In late March, North Vietnamese forces captured a critical bridge on Highway 1, the main north-south artery into Da Nang. They flew their communist flag from the position.

Another company from Fleming’s battalion tried to retake the bridge but got pinned down by heavy fire. Fleming dispatched his best platoon commander, a lieutenant named Mike Myers, and his men to help out.

Myers approached a Marine tank on the road, grabbed the external communication phone on the tank’s rear and coordinated directly with the tank commander. He ordered the tank to advance to the bridge’s edge while his platoon moved through a drainage gully nearby, using the tank’s bulk and firepower as a shield.

“The tank supported them, fired on the position, then they assaulted the end of the bridge and took it,” Fleming said. “The NVA ran and jumped into the river.”

After the firefight ended, Myers marched his men back to the firebase. He formed his platoon in proper military formation, bloodied, exhausted, but victorious. Fleming went out to meet them.

“They formally presented me with this flag,” Fleming said. “I felt so good that they thought of me and had done such a superb job of taking that vital bridge. I was very humbled and impressed. It was something.”

The Realities of War

Late one night in April, Fleming led around 180 men from Echo Company on a complex midnight movement into a riverbed. Moving that many men silently through darkness into a tactical position tested every skill Fleming had learned as an infantry officer.

“Just as we got there, the shooting started,” Fleming said. “My point man came across this area where the NVA were using as a distribution point. Then they opened up.”

In the brief, violent firefight, Fleming’s Marines killed or scattered the NVA soldiers and captured a significant cache of supplies. But one North Vietnamese soldier lay on the ground, mortally wounded.

The wounded soldier was in obvious agony. One of Fleming’s corpsmen approached him, looked at the suffering enemy, then looked at his company commander.

“The corpsman asked me, ‘Can I give him the shot? Lessen the pain? Fleming recalled.

Fleming faced the kind of situation every commander dreads. They had just started what would be a long night of combat. If a Marine got hit, they’d need that morphine.

“I told him not to do it because the night was just starting and we’re going to need it,” Fleming said. “What if a Marine got shot? I feel so bad about that. I could have put him out of his misery. I still got that memory.”

Weeks later in May 1968, Echo Company participated in Operation Allen Brook, a massive sweep through Go Noi Island about 15 miles south of Da Nang. The area had become a major staging area for the 36th Regiment of the 308th NVA Division. Marines from multiple battalions, including 2/27, fought through the flat rice paddies and elephant grass in extreme heat, taking steady casualties from ambushes, booby traps and fortified positions.

At one point, the Marines started taking enemy mortar fire. Fleming and his men dove into a bomb crater for cover. Some engineers jumped into another crater. A mortar round exploded, throwing the engineers out of it, before another one killed them.

By June, when the 27th Marines rotated home after four months in country, Fleming still had seven months remaining on his 13-month tour.

North to the DMZ

Fleming was sent to 2nd Battalion, 4th Marines, one of the most storied units in the Corps. The battalion’s nickname, the “Magnificent Bastards,” dated back to World War II fighting through the harsh Pacific Theater.

Just weeks before Fleming arrived, the Magnificent Bastards had been decimated during the Battle of Dai Do. From April 30 to May 3, approximately 1,000 Marines from 2/4 and reinforcing elements fought an estimated 6,000 to 10,000 soldiers from the NVA’s 320th Division in house-to-house combat across a cluster of fortified villages. The three-day battle left 81 Marines dead and hundreds wounded.

Two company commanders including Capt. James E. Livingston and Capt. Jay R. Vargas both earned Medals of Honor for their heroism in the desperate fighting. The battalion desperately needed replacements, especially officers.

Fleming initially served as operations officer during Operation Scotland II, the follow-on to the dramatic siege of Khe Sanh that had dominated headlines earlier in 1968. The battalion established a firebase on the high ground overlooking the abandoned base, conducting continuous patrols and fire missions to engage NVA forces and disrupt their logistics networks.

In August, Fleming took command of Hotel Company. The battalion’s area of operations stretched across some of the most contested ground in Vietnam, the mountainous jungle along the Demilitarized Zone separating North and South Vietnam, key infiltration routes, and ridgelines that had seen repeated bloody fighting since 1966.

Fighting in the Jungle

The physical environment along the DMZ was dramatically different from Da Nang. Hotel Company operated on constant patrol through dense triple-canopy jungle covering steep mountains, sometimes inserting by helicopter but more often walking, always searching for an enemy who knew every trail and hiding spot.

“It was very difficult because it was hot, very humid,” Fleming said. “Some of the jungle we went through was rough terrain. We had to chop through it.”

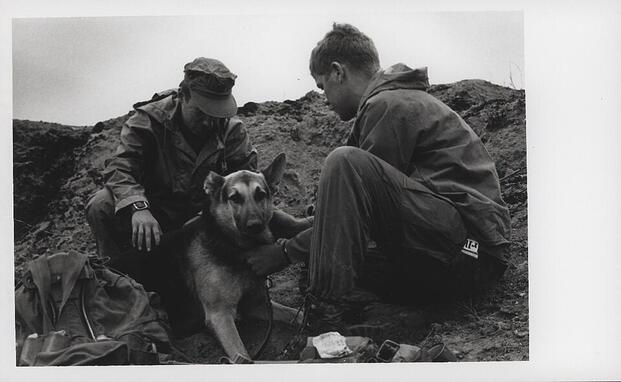

The area also teemed with dangerous wildlife. In certain areas, leeches swarmed the Marines the moment they entered the vegetation. Fleming had to keep a close eye on his men to ensure they did not get infections or fall ill during their patrols.

Marines in other units had even encountered tigers, one Marine was literally snatched and killed by a tiger while on patrol one night. During an operation near Con Thien in September, Fleming’s Marines discovered a massive snake that had just consumed a deer and couldn’t escape.

Basic survival became a challenge that had nothing to do with the enemy.

“We rarely ever got a whole meal,” Fleming said. “We relied on airlifts for water. Many times, you would have a dry canteen, and we went 30 days or so without taking a bath. Didn’t get a haircut for a month. Tried to shave but couldn’t.”

During one laborious movement through the jungle, Fleming decided to give his company a brief rest. He sat back against what looked like a harmless shrub. His radio operator immediately stopped him.

“He said, ‘Don’t move, skipper. Don’t move,” Fleming recalled.

There was a wire hanging from the shrub, connected to a grenade. It had been there for a long time; the wire was no longer tight, another incident of Fleming avoiding certain death.

In October, the regimental commander ordered Fleming to take Hotel Company on an extended long-range patrol deep into territory far beyond the range of supporting 105mm artillery.

“We went so far out they thought we got lost. They sent the commander out to find us,” Fleming said.

The patrol covered punishing terrain through 5,000-foot mountains covered in jungle so thick Marines had to hack through it. Fleming’s company found signs of NVA activity, trails, old fighting positions, cached supplies, but did not engage the enemy directly.

When they returned after days in the wilderness, the regimental commander personally congratulated the company for its extraordinarily difficult and dangerous movement. He put them in formation and shook every Marine’s hand.

Mutter’s Ridge: December 1968

Since August 1966, the ridgeline known as Mutter’s Ridge had seen countless battles. The Vietnamese called it Nui Cay Tri, “Bamboo Mountain,” a series of hills numbered 461, 484 and 400 that overlooked both the southern edge of the Demilitarized Zone to the north and Route 9 to the south. The ridge was a key infiltration route for NVA forces moving men and supplies from North Vietnam into the south.

Various Marine battalions had fought there since 1966 in an endless, bloody cycle, establishing bases, abandoning them, then fighting to retake them.

The ridge took its name from the radio call sign “Mutter” used by the 3rd Battalion, 4th Marines, which had first secured it during Operation Prairie in September and October 1966.

By early December 1968, intelligence indicated a North Vietnamese regiment, possibly the 1st Battalion, 27th NVA Regiment, had established positions along the ridge with well-prepared bunker complexes and reverse slope defenses that made them invisible to artillery and air strikes until the Marines were practically on top of them.

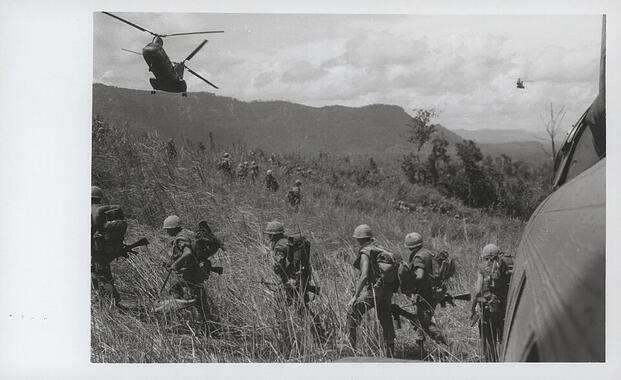

On Dec. 7, word came down for a major multi-battalion operation. Elements from across the 3rd Marine Division would assault the ridge in a coordinated sweep to clear out the NVA forces. Companies from 2/4 would insert by helicopter to different objectives.

Fleming had been scheduled to lead Hotel Company into one landing zone, but last-minute intelligence about explosions at another site redirected him to an alternate position. Fox Company went toward the ridge first, not knowing what awaited them.

Marines in Contact

The North Vietnamese had fortified their positions expertly. Dug into the ridgeline were bunkers with interlocking fields of fire, automatic weapons positioned to cover every approach, and mortar positions that could drop rounds anywhere on the hillside.

Fox Company took contact immediately. Automatic weapons fire ripped through the lead elements. Marines went down. Officers started calling for corpsmen. The company tried to maneuver, but everywhere they moved, more fire poured down.

The NVA showed no signs of breaking contact. The company was in serious danger of being overrun by a numerically superior force that held the high ground.

Fleming received urgent orders from the battalion to reach Fox Company before it’s too late.

His Marines hacked through vegetation with machetes, struggled up slopes slick with rain and rotting vegetation, fought for every meter of progress while knowing their fellow Marines were dying on the ridge ahead.

It took most of the day to reach the ridgeline, then Fleming’s Marines went to work.

Into the Fight

When Hotel Company finally got onto the ridge late in the afternoon of December 11, Fleming immediately assessed the tactical situation. It appeared as if the NVA were vacating their positions on the ridge.

Fleming ordered his men to dig in and prepare for an attack.

The North Vietnamese were actually in the process of executing a flanking maneuver to get around Fox Company’s exposed flank and encircle them. Then they ran into Fleming’s Marines.

The firefight erupted at close range.

Fleming’s Marines hit the enemy with rifles, machine guns and grenades. The fighting was intense but brief; the North Vietnamese, caught in the open during their maneuver, fell back. Hotel Company had blunted the assault.

“We managed to repel them, then we set in for the night,” Fleming said.

As night fell, both companies consolidated their positions along the ridgeline. At first light, the North Vietnamese attacked again.

The fighting was close, violent and chaotic. NVA soldiers emerged from bunkers and spider holes that Marines hadn’t even known were there. Automatic weapons fire swept the ridge. RPGs exploded against trees. Mortars started landing in the American positions.

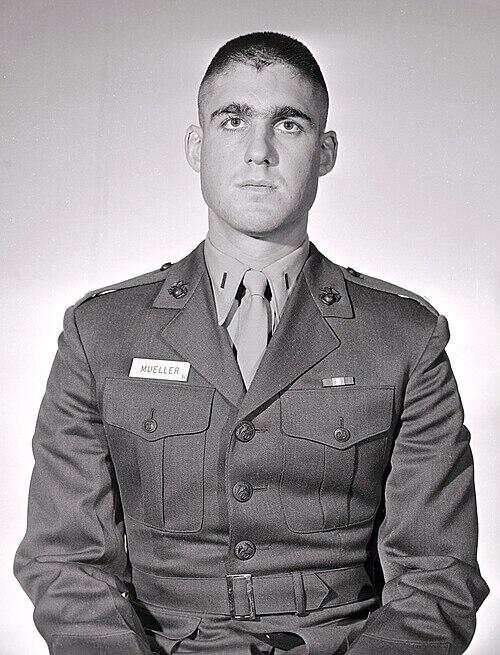

Among those in the thick of the fighting was 2nd Lt. Robert Mueller, a 24-year-old Princeton graduate who had enlisted in the Marines before earning his commission. Mueller had been in Vietnam less than a month, leading Hotel Company’s 2nd Platoon. Throughout the morning, he moved fearlessly from position to position, directing his Marines’ fire against the enemy.

At one point during the height of the firefight, a Marine fell forward of the friendly lines, mortally wounded. Mueller didn’t hesitate. He personally led a fire team across fire-swept terrain, rounds cracking past them, to reach the fallen Marine and drag him back. For Mueller’s actions that day, Fleming would recommend him for a Bronze Star with “V” device for combat valor.

But the dense jungle canopy prevented helicopter evacuations for wounded Marines. Some of the wounded Marines died waiting for a medevac.

Fleming called in every available fire support asset. With his artillery liaison officer beside him, he directed fire missions from multiple platforms across the operational area, 8-inch howitzers firing from bases miles away, 105mm and 155mm artillery, jet aircraft making strafing runs with 20mm cannons and dropping rockets, helicopter gunships with mini-guns, 81mm mortars from battalion positions.

The sounds of modern warfare overtook the ridge.

At one point, jet aircraft dropped napalm against NVA positions deeper in the jungle.

“Awesome stuff, using napalm,” Fleming said. “Only had that on one occasion. On the one hand, it’s a big spectacle in front of you, but also when you see it, you feel more comfortable. A sense of satisfaction, wow, this is going to protect us.”

As company commander, Fleming never fired his .45 pistol.

“I was too busy coordinating with my artillery liaison, calling in air strikes, mapping to get locations, using my compass,” Fleming said. “I had my hands full without shooting at the enemy. I never took my pistol out of my holster.”

During the fighting, a round struck Fleming’s Navy corpsman in the arm. The corpsman had been moving just behind Fleming, close enough to hear his commands.

“That bullet couldn’t have been more than a foot or less away from me,” Fleming said.

Fear in Combat

As the battle raged through the late morning, something bothered Fleming. He had been in firefights before, but this felt different.

The volume of fire was heavy. The NVA weren’t breaking contact. Every time the Marines tried to advance, more fire poured down from hidden positions.

“It didn’t dawn on me initially what was going on,” Fleming said. “But suddenly I realized, this is a really big enemy force on the DMZ. A regiment. And they could get reinforcements in quicker than we could.”

Hotel Company and Fox Company combined, roughly 200 Marines were engaging what intelligence estimated was an NVA regimental headquarters with possibly 1,200 to 1,500 enemy soldiers.

For the first time during his tour in Vietnam, Fleming felt something he’d never experienced in combat before, genuine, overwhelming fear.

“I got a little frightened,” he admitted.

For a moment, the weight of command and the tactical situation weighed on his mind. The NVA had the upper hand if they decided to commit everything they had.

“I had to calm myself and concern myself with other things, the battle, the casualties,” Fleming said. “You have other things to focus on. Your training kicks in.”

Fleming kept calling fire missions while directing his platoon commanders against the enemy.

The Aftermath of Mutter’s Ridge

By the time the firing finally died down that afternoon, the cost was high. Hotel Company had suffered four Marines killed and numerous wounded. Fox Company had taken even worse casualties, nine killed and 31 wounded.

The North Vietnamese had withdrawn deeper into the jungle, leaving the ridgeline in Marine hands. The battalion had captured one NVA warrant officer during the fighting. American firepower had inflicted heavy casualties on the enemy regiment. By any tactical measure, the Marines had won.

When the shooting stopped, Fleming’s Marines gathered all the killed in action and placed them in a bomb crater for collection. Standard operating procedure called for medevac helicopters to retrieve the dead for evacuation to Graves Registration. Fleming reported the grid coordinates of the crater to the battalion.

Then Hotel Company received new orders.

“My company was sent out of there because they wanted us to pursue the regiment we had been fighting,” Fleming said. “We were gone for a day or so.”

Fleming and his Marines moved out, following the trail of the withdrawing enemy, looking for blood trails, abandoned equipment, and any sign of where the NVA had gone. But the enemy retreated faster than Fleming’s men advanced.

About two days later, they returned to their original position. There, they found the bomb crater still filled with the bodies of the fallen Marines.

No evacuation helicopters had come, and no recovery team had arrived. For 48 hours, while Fleming’s company had been chasing the NVA through the jungle, these four Marines had been unceremoniously left in the crater.

“Then my company had the dubious task of calling in medevac helicopters,” Fleming said. “We had to load these Marines up that had been dead there in that crater for two days.”

When the helicopters finally arrived, Hotel Company loaded the bodies. The physical act of lifting their dead comrades into the aircraft was one of the most emotionally devastating moments of Fleming’s life.

“Talk about a somber group of Marines,” Fleming said. “That was the day that everybody got really upset, including me. I don’t know what happened or why they were not retrieved. We had won the battle.”

Although the Marines had secured the ridge from enemy forces while inflicting heavy losses on the NVA, the Marines were demoralized by the incident.

The Magnificent Bastards

Despite the brutal conditions, grinding patrols and constant danger, Fleming developed profound respect for the Marines he commanded.

“My Marines, they were young, young Marines, but I had the greatest admiration for them. Whatever I needed done, they would do it without hesitation. I thought they were magnificent. They didn’t look like it, but they acted like it.”

One young Marine epitomized the spirit Fleming admired. Someone sent the Marine a small Christmas tree prior to the operation on Mutter’s Ridge. He strapped it to his pack and refused to part with it, carrying it with him through the battle.

“He had it strapped to his pack the entire time until Christmas. We were there the whole time. I had to laugh. He was so dedicated to the spirit of Christmas.”

By February 1969, Fleming had been in combat for 13 months. His battalion commander wanted him to extend for six months. Many officers did, combat pay was good, and the experience was invaluable for career advancement.

Fleming refused.

“I told him I’m getting too careless, too used to it,” Fleming said. “I was getting so used to the combat environment that it was like second nature. I don’t know what would happen if I stayed. I felt like if I did, something bad would happen.”

Most Marines got two tours in country. Better to go home, reset and come back in a year.

Leaving proved emotionally wrenching. A helicopter extracted Fleming from a hill overlooking Laos. He parted ways with his Marines as they stayed behind, continuing their operations along the DMZ. They gifted him an enemy SKS semi-automatic rifle as he left. A huge battle would erupt on that same hill shortly after.

“I felt bad,” Fleming said. “It was hard to leave. There was a huge burden that was off my shoulders when I got back to civilization after 12 or 13 months living like an animal. But I was reluctant to leave.”

Fleming flew home in February 1969, at a time when anti-war protests had reached their peak. Peace protestors routinely spat on and harassed service members returning from Vietnam. He walked through San Francisco International Airport in uniform, carrying a rifle.

“Nobody bothered me when I went through the airport with that rifle,” Fleming said. “No one said anything either. No one ever said anything or threw eggs at me, but no one thanked me either.”

His parents were proud of his service, but conversation about Vietnam remained limited.

“You go away for a while, come back, and that was it. My parents were proud of me, but no one ever asked me about it or said anything,” he said.

Fleming’s Marine Corps Career

Fleming never returned to Vietnam for a second tour as he expected. The war drew down and ended before he could.

He went on to serve as an aide to a general at Camp Lejeune. Some of his former Vietnam platoon commanders helped him land that assignment. He also spent time as an instructor at The Basic School at Quantico, teaching new lieutenants the infantry tactics and leadership skills that might keep them alive in combat.

It was at Quantico that Fleming reconnected with Robert Mueller, who had also become an instructor after recovering from wounds received during another firefight in April 1969. He also met and worked alongside Wesley Fox, Medal of Honor recipient from the 1st Battalion, 9th Marines.

Later assignments took Fleming to the Pentagon, where he worked in the Joint Chiefs of Staff manpower and personnel section, briefing the JCS on manpower issues.

He also served multiple tours at Fleet Marine Force Pacific headquarters in Hawaii, working in plans and as staff secretary.

Fleming eventually retired in 1984 as a lieutenant colonel after 22 years of service.

He then spent 17 years at Hawaii Pacific University as associate vice president for student services. During this time, he also earned a master’s degree in military studies, studying under instructors who included former four-star generals.

Fleming had a son who followed him into the Marine Corps, serving as a captain during the Gulf War. He also reached out to and briefly kept in touch with Mueller, who went on to become the director of the FBI.

Today, at 84, Fleming lives in El Paso, Texas, helping raise his grandchildren.

A Marine Corps Vietnam Veteran

Fleming has visited the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C., twice. Both times, he found the names of the Marines he lost etched into the black granite.

“I’ve seen all the names of the people I know on the wall that are there,” he said.

LCpl. Robert W. Cromwell, LCpl. John C. Liverman, Cpl. Agustin Rosario, Cpl. James O. Weaver were his Marines killed on Mutter’s Ridge.

“I honor them by telling people to thank them for what they did. They were there and fought and gave their lives for their country,” he said. “These guys, regardless of motivation, were there and gave their lives.”

More than five decades after leaving Vietnam, Walter Fleming’s identity remains inseparable from the Marine Corps.

“It is me. I am a Marine,” Fleming said. “It dominates my life. I can’t get away from it even if I wanted to. All my friends are Marines. We all share the same experiences in most cases. I’m proud to be a Marine, proud to say I served in Vietnam, proud I know these guys that did the same thing.”

But the experience fundamentally changed how he views war and its costs.

“I do know one thing, war does not solve any problems,” he said. “If possible, it should be avoided.”

All of his experiences from Vietnam remain vivid. From the first two Marines he lost in country, to the Battle on Mutter’s Ridge and his decisions as a company commander. All of it shaped who Walter Fleming became.

“To this day,” he said, “I still think about that.”

Read the full article here

16 Comments

The fact that Fleming witnessed two Marine helicopters collide mid-air during an amphibious assault exercise off the coast of Spain, killing several Marines, must have been a sobering moment for him, making him realize the dangers of military service.

This incident likely prepared him for the harsh realities of war he would later face in Vietnam.

Captain Walter Fleming’s experience of surviving 13 months of combat in Vietnam without a scratch is a testament to his bravery and luck, given that he was within the lethal blast radius of two mine detonations near Da Nang.

The chaos Fleming encountered upon arrival in Vietnam, with officers and enlisted Marines crammed together without separation or guidance, highlights the disorganization and challenges faced by the military during the Tet Offensive.

This lack of organization must have added to the apprehension and fear of the unknown that Fleming felt before deploying.

Fleming’s background, with his father spending 24 years in the Coast Guard, including service during WWII, likely influenced his decision to join the military and his approach to leadership.

Fleming’s decision to join the Marine Corps through the Platoon Leaders Class, despite having a business degree from Florida State University, shows his commitment to serving his country amidst the looming draft and the Vietnam War.

It’s notable that Fleming’s apprehension about deploying to Vietnam stemmed from a fear of the unknown, which is a common sentiment among soldiers facing their first combat deployment.

Fleming’s story serves as a reminder of the sacrifices and dangers faced by military personnel and their families during the Vietnam War, and the importance of acknowledging their service and experiences.

The fact that Fleming commissioned in January 1963 as an infantry officer and went on to command an 81mm mortar platoon on deployments to the Caribbean and Mediterranean, shows his rapid progression and adaptability within the Marine Corps.

The transition from being a Combat Cargo Officer on a naval ship to commanding Echo Company in a combat zone would have required significant adjustment and flexibility from Fleming.

I’m curious about the psychological impact of Fleming’s experiences, especially considering he was within the lethal blast radius of explosions twice and yet walked away uninjured, on his mental health and worldview.

It would be insightful to explore how such close calls affect a person’s perspective on life and death.

The reactivation of the 27th Marines at Camp Pendleton and their rushed deployment to Vietnam underscores the urgent need for reinforcements during the Tet Offensive.

Fleming’s assignment to the 2nd Battalion, 27th Marines, and his role in patrolling the ‘rocket belt’ around Da Nang Air Base, demonstrates the critical missions undertaken by the Marines to secure key installations.

It’s interesting that Fleming spent his first years as a Marine Officer with the 2nd Battalion, 8th Marines before deploying to Vietnam, which suggests that his initial experiences shaped his leadership skills.