Listen to the article

As World War II drew to a close, U.S. Navy intelligence suspected German U-boats equipped to launch V-1 rockets were preparing to hit New York City. The War Department dismissed the threat. The Navy disagreed and launched Operation Teardrop.

In the final weeks of the war, the Navy hunted down and sank five German submarines in the North Atlantic. They stopped what they believed was an imminent attack on the East Coast. The victory came at a cost. The last American warship lost in the Atlantic fell to a German torpedo. Desperate to confirm the missile threat, Navy interrogators brutally tortured the captured German crews, casting a shadow over the Navy’s last success in the Battle of the Atlantic.

Intelligence Sparks the Hunt

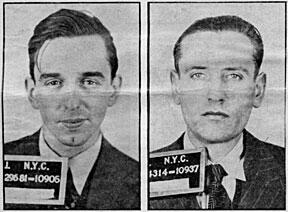

Two captured spies may have triggered the sudden operation. William Colepaugh and Erich Gimpel landed in Maine from U-1230 in late November 1944. Within weeks, they were captured and ended up in FBI custody. Their interrogators learned a shocking revelation.

Germany was preparing several submarines to be equipped with V-1 rockets, the spies allegedly reported. The weapons would strike New York and other East Coast cities soon.

The intelligence reached Navy commanders not long after. Mayor of New York City Fiorello La Guardia even went public with the warnings. As the public became fearful, the War Department dismissed the threat. Army officials told President Franklin Roosevelt the probability was too low to justify diverting resources on a ghost hunt.

The Navy disagreed.

Vice Admiral Jonas Ingram commanded the Atlantic Fleet. He called reporters to a warship in New York Harbor on January 8, 1945. The admiral warned that missile attacks were possible. He announced that naval forces were assembling to counter the submarine-launched weapons.

German propaganda amplified American fears. Minister of Armaments Albert Speer made a broadcast that January. He claimed V-1 and V-2 missiles would fall on New York by February 1. That was enough proof for the Navy.

Meanwhile, intelligence analysts studied reconnaissance photographs of German sub pens in Norway. Strange mountings appeared on several submarines. Some officers concluded they were wooden tracks for loading torpedoes. Others remained unconvinced, believing they were rocket railings.

Prior to that, German engineers had conducted underwater sub-based rocket tests in June of 1942. Kapitänleutnant Friedrich Steinhoff commanded submarine U-511 during the experimental trials near Greifswalder Oie. The trials proved rockets could launch from submerged platforms. Development ended in early 1943 as military commanders realized the system degraded the seaworthiness of U-boats.

Allied commanders in 1945 were unaware that the program had died.

Gruppe Seewolf Crosses the Atlantic

Nine Type IX submarines left Norway in mid-March 1945. Seven of them formed Gruppe Seewolf. Their mission was attacking shipping off the American coast. The goal was diverting Allied anti-submarine forces away from British waters, where German boats faced devastating losses.

American code-breakers tracked every movement. British intelligence had cracked German Enigma encryptions years earlier. Signals revealed departure dates, courses, and destinations. Given the previous intelligence reports, Allied commanders were concerned.

Ingram and Tenth Fleet staff concluded the boats likely carried V-1 flying bombs. They designated the response Operation Teardrop. The Atlantic Fleet assembled two massive barrier forces to stop the subs.

Each task force included two escort carriers and more than twenty destroyer escorts. They would form patrol lines across the North Atlantic. Any submarine approaching American waters would face overwhelming firepower well before reaching the coast.

The First Barrier Force sortied from Hampton Roads between March 25 and 27. The ships refueled at Naval Station Argentia in Newfoundland. Twelve destroyer escorts formed a line 120 miles long east of Cape Race by April 11. Escort carriers Mission Bay and Croatan patrolled behind them.

Heavy seas hampered air operations. Aircraft struggled to launch and recover in the Atlantic’s spring storms. The weather even forced the submarines to remain submerged, slowing their westward progress.

Gruppe Seewolf pressed on anyway. The boats ultimately found no targets. Convoys had been routed far south to avoid both weather and submarines. The lack of targets forced them to continue pushing toward the American defense line.

The Final Loss

Destroyer escort USS Frederick C. Davis made sonar contact on April 24. The target appeared at 2,000 yards. Sound operators reported a sharp, clear echo.

The destroyer and the USS Hayter turned to engage the target, but lost contact with the sub. As they regained contact, the sub already had them in its sights.

U-546 fired first. An acoustic torpedo struck the port side of Frederick C. Davis at 8:39 a.m. The explosion tore through the forward engine room. Five minutes later, the ship broke in two.

Ensign Philip Lundeberg assisted with damage control in the stern section. The crewmen fought desperately to maintain watertight integrity.

Before the stern sank, the sailors managed to safe all but two depth charges. The charges exploded underwater as the section went down. Concussive shockwaves killed many swimmers.

“I was in the water at the time, and I had a rather severe pain in my stomach,” Lundeberg later recalled. “It felt as if my insides were being twisted around.”

Rescue ships recovered several survivors from the frigid water. Many waited three hours for pickup. The ship’s complement numbered 192. A total of 126 died. Frederick C. Davis became the last American warship sunk in the Atlantic theater.

Nearby escorts immediately counterattacked. Destroyer escorts Flaherty, Hayter, Neunzer, Janssen, Pillsbury and Varian pursued U-546 for more than ten hours. They dropped depth charges and fired hedgehog projectiles. The submarine finally surfaced at 6:44 p.m., heavily damaged and unable to dive.

American gunfire destroyed the boat within minutes. Rescue crews pulled 33 Germans from the water, including commander Paul Just. Four other U-boats (U-1235, U-880, U-518, U-881) were intercepted and sank with their entire crews during Operation Teardrop while the others escaped. U-546’s survivors would provide the only chance to confirm or deny the missile threat.

The Interrogations

Eight U-546 specialists were separated from other prisoners immediately after rescue. The Navy sent them to isolation at Naval Station Argentia. Regular prisoners went to standard POW camps. The specialists faced something different than their comrades.

Two interrogators arrived on April 28. One wore a Navy captain’s uniform but was apparently a civilian agent. They likely came from the joint Army-Navy facility at Fort Hunt, Virginia.

Tenth Fleet records described what followed. The Germans proved “extremely security conscious.” They refused to divulge information Allied intelligence already possessed through Enigma decrypts.

Just faced “shock interrogation” on April 30. The exact methods of the interrogation remain unknown. Records show he ended up unconscious, before waking sometime later.

The beatings continued after transfer to Fort Hunt. All eight men endured harsh treatment until Just agreed to write an accurate account of U-546’s history on May 12. Germany had already surrendered four days earlier.

Philip Lundeberg, who survived the sinking of the Frederick C. Davis, went on to become the American naval historian and curator emeritus of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History.

He later characterized the treatment in stark terms. The beatings and torture constituted a “singular atrocity,” he wrote. Interrogators needed information quickly. They believed missile attacks were imminent.

Many of the records in Fort Hunt were burned after the war. Full details of what happened disappeared with them.

The Navy interrogated more prisoners after Germany’s surrender. U-805 and U-858 survived Gruppe Seewolf. Both boats surrendered at sea at the end of the war. Their crews confirmed they carried no missile equipment.

U-873 surrendered on May 11 as it made its way to the Caribbean. Steinhoff commanded the boat. His capture guaranteed intense questioning as interrogators knew about his role in the 1942 rocket tests.

Steinhoff faced brutal treatment at Charles Street Jail in Boston. His initial defiance eventually gave way. He provided information, though nothing suggested missile attacks had ever been planned.

A Navy investigation was opened shortly afterward. Steinhoff committed suicide on May 19, 1945 before it was concluded.

The Truth Emerges

Postwar analysis eventually unveiled the truth. Germany had explored submarine-launched weapons repeatedly, though none reached operational status.

The 1942 tests used short-range artillery rockets. They could fire underwater but couldn’t be aimed effectively. The launch system reduced submarine maneuverability, so the Germans cancelled the program.

German engineers revisited the concept in late 1943. Bodo Lafferenz proposed launching V-2 ballistic missiles from towable containers. A submarine would tow the container to within 186 miles of the target. The container would then be positioned vertically for launch.

Work began in November 1944. Construction was completed on one container at Schichau Dockyard in Elbing. The project never progressed beyond that single prototype. Technical challenges proved insurmountable. Container stability during launch remained unsolved. Missile accuracy presented problems German engineers couldn’t overcome.

Gruppe Seewolf carried conventional torpedoes and nothing else. The submarines had been dispatched simply to attack shipping, not launch rockets at New York.

Albert Speer’s propaganda broadcast had been exactly that. Propaganda. No capability existed to fulfill his threats, though his speech occurred at a moment when Allied analysts worried of the potential sub-based missiles could pose.

The captured spies’ information proved unreliable. Colepaugh and Gimpel likely repeated rumors they had heard in Germany. Their mission focused on gathering technical intelligence, not military operations. Neither had access to accurate information about submarine capabilities. It is unknown if the men actually divulged anything concrete about German submarine operations.

Legacy and Lessons

Operation Teardrop succeeded in its primary mission. Five of seven Gruppe Seewolf boats never reached American waters. U-881 became the last German submarine sunk by U.S. Navy forces. Destroyer escort Farquhar destroyed it with depth charges on May 6.

The operation demonstrated the power of signals intelligence. Enigma decrypts enabled the precise tracking of submarine movements. Ships could position themselves based on intercepted radio traffic. The barrier forces knew where to patrol before the submarines even arrived.

Lundeberg assessed Teardrop as a “classic demonstration” of coordinated hunter tactics. British experience contributed to American methods. Communications intelligence proved critical to intercepting the U-boats.

The treatment of the prisoners cast a shadow over that success. The torture violated standards the Navy normally upheld. Lundeberg’s characterization as a “singular atrocity” came from someone who had every reason to hate U-546’s crew. Yet he still condemned what American interrogators did.

The desperation driving those interrogations reflected genuine fear. Intelligence officers believed American cities faced imminent attack. The pressure didn’t excuse the treatment, but it explained the motive.

Ultimately, the Navy began its own submarine-launched missile program almost immediately after the war. Engineers studied German research materials. They examined captured documents about the V-1 and V-2 programs.

The submarine USS Cusk received several modifications in 1947. Workers installed a missile hangar on the ship. A launch ramp extended aft. The submarine would surface to prepare and fire the weapons.

Cusk launched the first submarine-based guided missile on February 12, 1947. The weapon was a Loon, an American copy of the V-1 flying bomb. The project proved submarines could serve as mobile launch platforms.

The concept evolved rapidly. Regulus missiles replaced Loons. Nuclear propulsion eliminated the need for surfacing. Ballistic missiles superseded cruise missiles. Polaris boats became cornerstone weapons of Cold War deterrence. Every advancement traced back to wartime German experiments and postwar American determination to perfect what Germany had failed to achieve.

Gruppe Seewolf represented the last German U-boat offensive against American shores. While they never fired rockets at the continental U.S., those fears drove innovation that shaped naval warfare for generations.

Frederick C. Davis remains the last U.S. warship lost in the Atlantic during WWII. Her 126 dead include the final American naval casualties of the European war. They died hunting what they believed was a dangerous threat to their homeland.

Read the full article here

21 Comments

The role of intelligence gathering in Operation Teardrop highlights the importance of accurate and timely information in military decision-making.

The use of reconnaissance photographs of German sub pens in Norway was a key factor in gathering intelligence about the German program, and demonstrates the importance of surveillance in modern warfare.

The experimental trials conducted by Kapitänleutnant Friedrich Steinhoff in 1942 proved that rockets could launch from submerged platforms, which must have been a significant breakthrough at the time.

I wonder what would have happened if the German program to develop submarine-launched rockets had not been terminated in early 1943 due to concerns about the seaworthiness of U-boats.

The role of Mayor of New York City Fiorello La Guardia in going public with the warnings about the potential missile attack on the city must have contributed to the growing fear among the public.

The story of Operation Teardrop is a reminder of the complexities and challenges of warfare, where military commanders must make difficult decisions based on limited intelligence.

Vice Admiral Jonas Ingram’s decision to assemble naval forces to counter the submarine-launched weapons was a bold move, considering the War Department’s skepticism.

The claim made by Minister of Armaments Albert Speer that V-1 and V-2 missiles would fall on New York by February 1, 1945, must have added to the fear and tension among the American public.

I’m curious about the experimental trials conducted by German engineers in June 1942, where they tested underwater sub-based rocket launches near Greifswalder Oie.

The loss of the last American warship in the Atlantic during Operation Teardrop is a reminder of the sacrifices made by the military during World War II.

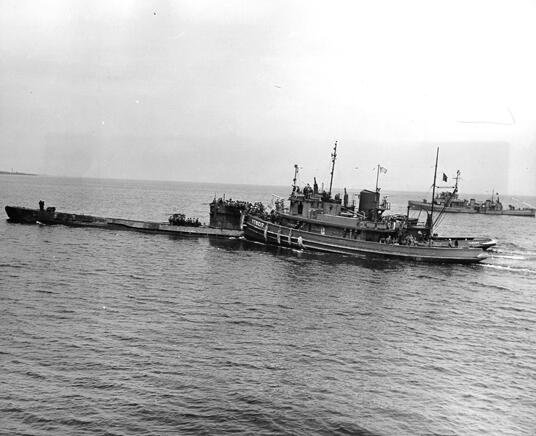

The image of the Type IX submarine with its double hull and wide upper deck is a testament to the advanced design of German U-boats during World War II.

The story of Operation Teardrop highlights the importance of intelligence gathering and the need for military commanders to take threats seriously, even if they seem unlikely.

It’s concerning that Navy interrogators brutally tortured the captured German crews to confirm the missile threat, which casts a shadow over the Navy’s victory in the Battle of the Atlantic.

I’m skeptical about the effectiveness of the Navy’s strategy to counter the submarine-launched weapons, given the limited intelligence they had about the German program.

The image of the Type IX and Type VII submarines highlights the differences in their designs, with the larger Type IX having a double hull and wide upper deck.

The fact that the War Department dismissed the threat of German U-boats equipped with V-1 rockets is surprising, given the intelligence gathered from captured spies William Colepaugh and Erich Gimpel.

The role of the FBI in interrogating the captured spies William Colepaugh and Erich Gimpel must have been crucial in gathering intelligence about the German program.

The fact that the Navy sank five German submarines in the North Atlantic during Operation Teardrop is a significant achievement, but it came at a cost, including the loss of the last American warship in the Atlantic.

It’s interesting to note that the intelligence analysts studied reconnaissance photographs of German sub pens in Norway, which showed strange mountings that some believed were rocket railings.

I’m curious about the fate of the captured German crews who were interrogated by the Navy, and what happened to them after the war.

It’s concerning that the Navy’s victory in the Battle of the Atlantic was marred by the brutal treatment of captured German crews, which raises questions about the morality of war.