Listen to the article

Ten thousand armed coal miners held Blair Mountain in late August 1921. They faced machine gun nests, private planes dropping bombs, and a growing force of deputies backed by coal company money. Then President Warren Harding made a decision that would end the largest armed insurrection since the Civil War.

He sent in the U.S. Army.

The Battle of Blair Mountain as it is now known, became the most infamous event of the West Virginia Coal Wars. In response, the federal government deployed troops, bombers, and military force to suppress American workers fighting for union rights. The intervention set a precedent that would shape how the military handled domestic unrest for decades.

A System Built on Control

West Virginia’s coal miners lived under what historians call an industrial police state. They worked in company-owned mines, lived in company-owned houses, and shopped at company-owned stores. Wages came as scrip, company currency worthless anywhere else. Miners rented tools from the company, bought overpriced goods from company stores, and fell deeper into debt with each paycheck.

Death rates in West Virginia mines were the highest in the nation. In 1918 alone, 404 miners died in the state. Gas explosions, roof collapses, and mechanical accidents killed thousands over the years. Safety regulations barely existed. Coal operators prioritized production over lives.

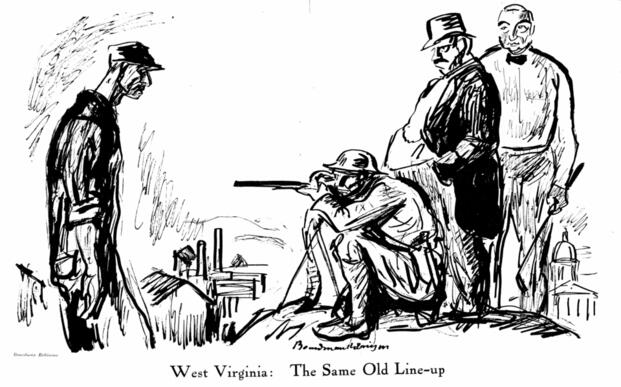

When miners tried to organize unions, companies deployed the Baldwin-Felts Detective Agency. These private agents functioned as hired muscle. They beat organizers, evicted families at gunpoint, and even killed union sympathizers. Mine guards patrolled towns on horseback carrying shotguns, rifles, and clubs. Free speech didn’t exist. Miners couldn’t gather in groups larger than two. Company postmasters read and censored their mail.

Making conditions worse, the coal operators controlled local sheriffs, judges, and politicians. The system was designed to crush any resistance before it started.

The Shooting in Matewan

On May 19, 1920, Baldwin-Felts agents arrived by train in Matewan, a small mining town in Mingo County. They came to evict miners from company housing for trying to unionize. Matewan Police Chief Sid Hatfield and Mayor Cabell Testerman confronted them, demanding to see warrants.

The agents couldn’t produce legal documentation. Hatfield deputized several miners on the spot to stop the evictions. Tensions exploded into a gunfight along the railroad tracks. When the shooting stopped, 10 people lay dead including the mayor, seven Baldwin-Felts agents, and two miners.

Hatfield became an instant hero across West Virginia’s coalfields. He had stood up to the coal companies. Miners saw hope that resistance was possible.

The companies saw a threat that needed to be eliminated.

Violence escalated throughout 1920 and into 1921. State police raided miner tent colonies, destroying shelters and arresting union members. Governor Ephraim Morgan declared martial law in Mingo County at the coal operators’ request. Hundreds of union activists were jailed without trial. Families were assaulted in makeshift camps.

By the summer of 1921, West Virginia was a powder keg.

The Conflict

On August 1, 1921, Hatfield walked up the steps of the McDowell County courthouse with his friend Ed Chambers. Both men were unarmed. Their wives accompanied them. Baldwin-Felts agents opened fire from the top of the stairs. Hatfield died instantly. An agent ran down and shot Chambers again in the back of the head while his wife screamed.

None of the assassins faced charges.

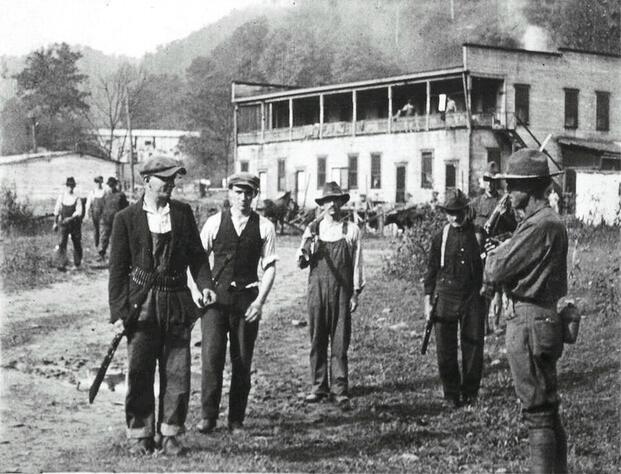

Word spread through the mining camps like wildfire. Within days, miners began gathering at Lens Creek. By August 24, roughly 13,000 armed men started marching south toward Mingo County. Many were World War I veterans. They knew how to fight.

“It is time to lay down the bible and take up the rifle,” declared John Wilburn, a Baptist minister and part-time miner who would lead troops up Blair Mountain.

The miners wore red bandanas around their necks to identify each other in the dense forests. The press called them the “Red Neck Army.” They commandeered trains, including one they renamed the “Blue Steel Special.” Their goal was to free imprisoned union miners in Mingo County, end martial law, and force the coal operators to recognize their rights.

One obstacle stood in their way. Logan County Sheriff Don Chafin had assembled a private army of 3,000 men along Blair Mountain’s ridgeline. The Logan County Coal Operators Association paid for everything, creating the nation’s largest private armed force.

“No armed mob will cross the Logan County line,” Chafin proclaimed.

President Harding Intervenes

On August 25, Secretary of War John Weeks sent Brigadier General Henry Bandholtz to West Virginia with presidential approval. Harding chose carefully. Bandholtz had earned his reputation suppressing resistance to American occupation in the Philippines. He later served as Provost Marshal for the American Expeditionary Force in France during World War I. The 56-year-old general knew how to put down rebellions.

Bandholtz carried explicit orders to determine whether federal troops were necessary or if the threat alone would suffice. He was to restore order without delay, preferably without bloodshed.

He met with Governor Ephraim Morgan first. Morgan claimed the southern counties were at the mercy of an army of rabble. Only military intervention would prevent massive loss of life and property destruction.

Then Bandholtz met with union leaders Frank Keeney and Fred Mooney on August 26. He made his position crystal clear. He wasn’t interested in labor disputes or mining conditions. He told them he was “indifferent to the merits of the dispute between miners and coal operators” but cared only about the president’s directive to restore law and order.

If the miners didn’t disperse, Bandholtz warned, the U.S. Army would “snuff them out” or arrest them for treason.

Keeney relayed the warning to miners gathered at a baseball field in Madison.

“You can fight the government of West Virginia, but, by God, you can’t fight the government of the United States,” he told them.

The miners initially agreed to turn back. Then reports arrived that Chafin’s forces had attacked union sympathizers in Sharples, killing miners and endangering families. The march resumed with renewed fury.

Bandholtz reported back to Washington with the news that federal intervention was necessary.

Four Days of Combat

Fighting erupted on August 31 when Wilburn led 70 miners up Blair Mountain before dawn. They encountered three deputy sheriffs, including John Gore, a notorious mine guard. Gunfire broke out. Gore fell dead with a bullet in his head. One miner, Eli Kemp, also died in the skirmish.

Soon, gunfights broke out all along the mountain.

The battle raged for four days across a 15-mile ridgeline. Chafin’s forces held superior positions and better weapons. Private planes dropped homemade bombs filled with gunpowder, nuts, and bolts. They also allegedly dropped poison gas and explosives left over from World War I.

An estimated one million rounds were fired over that short time period. The miners pushed forward repeatedly, at times coming within four miles of Logan. Military strategists would later note that the miners, many trained in WWI tactics, had nearly broken through Chafin’s defenses.

But they wouldn’t get the chance.

The Largest Domestic Military Deployment in Decades

On August 30, President Harding issued a proclamation commanding all persons engaged in the insurrection to disperse. He threatened military force. Two days later, he ordered the deployment.

The response was massive. Harding mobilized 2,500 Army troops under Bandholtz’s command, the largest domestic military deployment in over 40 years. He sent Army Air Service reconnaissance planes to patrol the skies and gather intelligence. Most dramatically, he dispatched Martin MB-1 bombers from Maryland under General Billy Mitchell, the same aviation pioneer who would later advocate for expanded air power.

The bombers never dropped ordnance on the miners. Their mission was surveillance and intimidation. One Martin bomber crashed on its return flight, killing four of the five crew members.

By September 3, federal troops poured into West Virginia. They established positions at Blair Mountain, Jeffrey, Sharples, and Logan. Soldiers built posts along the ridgelines. Bombers circled overhead. The military occupation was swift and overwhelming.

Governor Morgan issued a proclamation ordering peace officers to cooperate with U.S. troops “to the end that there may be unity of action.” State and federal authority now stood united against the miners.

Veterans Face Veterans

The miners faced an impossible predicament. Many had fought for their country in France just three years earlier. Now Army troops, their fellow veterans, stood between them and their goals. The miners were unwilling to fight the U.S. Army.

They laid down their weapons.

Some scattered fighting continued until September 4, but the rebellion was over. Roughly 1,000 exhausted miners surrendered directly to Army troops. The rest hid their rifles in the woods and returned home, hoping to avoid arrest.

Bandholtz refused Governor Morgan’s request to use the Army forces to help civil authorities arrest the rest of the miners. His job was restoring order, not prosecuting workers. But he did establish censorship over news reports, removing descriptions of poverty conditions in mining towns. When journalist Boyden Sparkes tried to publish sympathetic coverage after being shot twice by state militia, Army censors told him, “No sob stuff for those red necks.”

By the end of the Battle of Blair Mountain,16 people were dead, including 12 miners and four of Chafin’s men. Hundreds more were wounded. The true death toll may have been much higher. Miners hid their casualties to avoid revealing losses to the enemy. Some bodies were likely buried in secret on the mountain.

The Aftermath

West Virginia authorities indicted 985 miners on charges ranging from murder to treason against the state. Union leader Bill Blizzard faced treason charges in three separate trials in Charles Town, Lewisburg, and Fayetteville before prosecutors finally gave up. Most miners were eventually acquitted by sympathetic juries, though some served up to four years in prison.

Chafin, the sheriff who sparked much of the violence, was arrested several years later on corruption charges. He served time in federal prison for bootlegging, confirming what miners had claimed all along about Logan County’s corruption.

At a later trial, some of the coal miners provided an unexploded bomb from the battle to argue that state authorities deployed excessive force against them.

The Battle of Blair Mountain established concrete precedents for military intervention in domestic labor disputes. When the Bonus Army of World War I veterans marched on Washington in 1932 demanding payment for the combat service, President Hoover deployed Army troops under Douglas MacArthur to drive them out. The military response mirrored Bandholtz’s actions in West Virginia, using overwhelming force, swift action, and no negotiation against American civilians, including veterans.

It was the first use of military aircraft for domestic surveillance and intimidation. The Army going forward felt that overhead planes could compel rioters or rebels to disperse without shots being fired.

The intervention crushed the United Mine Workers in West Virginia. Membership collapsed across Appalachia. Coal operators tightened their grip on mining towns, and safety conditions deteriorated. Death rates in West Virginia mines during the 1920s reached over 400 miners per year, the highest in state history.

Union organizing wouldn’t recover in West Virginia’s coalfields until Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal in the 1930s. The National Labor Relations Act of 1935 finally gave workers legal protections that the miners at Blair Mountain had fought for at gunpoint.

The largest armed insurrection on American soil since the Civil War ended in favor of the coal bosses, after 16 people were killed. The Battle of Blair Mountain was one of the largest domestic uprisings and civil conflicts in American history, put down by the overwhelming deployment of federal troops to West Virginia.

Read the full article here

21 Comments

The system of control in West Virginia’s coal mines, where workers lived in company-owned houses and shopped at company-owned stores, sounds eerily like a form of modern-day feudalism.

It’s amazing how the companies managed to exert such total control over every aspect of the miners’ lives, from their wages to their living arrangements.

The Battle of Blair Mountain was the largest armed insurrection since the Civil War, and yet it’s a relatively unknown event in American history – why do you think that is?

I’m concerned about the legacy of the West Virginia Coal Wars and the ongoing struggles of miners and laborers today – what can we learn from this history?

The death of 10 people in the shooting in Matewan, including the mayor and seven Baldwin-Felts agents, marked a turning point in the conflict – what were the immediate consequences of this event?

The fact that President Warren Harding sent in the US Army to suppress the miners’ uprising is a stark example of the government’s priorities at the time – what were the long-term consequences of this decision?

The fact that the coal operators controlled the local postmasters and censored the miners’ mail is a clear example of the level of surveillance and control exerted over the miners – what were the consequences for those who spoke out against the companies?

I’m curious about the role of Sid Hatfield, the Matewan Police Chief who deputized miners to stop the evictions – what happened to him after the shooting in Matewan?

The death toll in West Virginia mines was the highest in the nation, and yet the coal operators prioritized production over lives – what were the economic pressures that drove this prioritization?

I’m skeptical about the claim that the US Army’s intervention in the Battle of Blair Mountain set a precedent for handling domestic unrest – what other examples are there of the military being used in this way?

The US Army’s deployment of bombers and 2,500 troops to crush the miners’ uprising is a stark example of the military’s role in maintaining domestic order – what are the implications of this event for modern-day labor movements?

The coal operators’ use of private agents to beat organizers and evict families at gunpoint is a clear example of the violent means used to maintain control – what were the consequences for these agents?

The fact that 404 miners died in West Virginia mines in 1918 alone is staggering, and it’s no wonder they were desperate for union rights and better working conditions.

It’s even more shocking when you consider that safety regulations barely existed at the time, making it a miracle that more didn’t die.

The image of mine guards patrolling towns on horseback carrying shotguns, rifles, and clubs is a powerful symbol of the intimidation and fear that miners lived under.

It’s no wonder that free speech didn’t exist in these towns, given the level of militarized control exerted by the coal companies.

It’s striking that the coal operators controlled local sheriffs, judges, and politicians, essentially creating a system designed to crush any resistance before it started.

This level of corruption and control is what led to the miners’ desperation and ultimately the deployment of the US Army to suppress the uprising.

The fact that miners were paid in scrip, company currency worthless anywhere else, is a clear example of exploitation – how did this practice affect their ability to improve their living conditions?

I’m curious about the role of the Baldwin-Felts Detective Agency in suppressing unionization efforts – were they essentially a private militia for the coal companies?

The system of control in West Virginia’s coal mines was designed to keep miners in debt and unable to organize – how did this system ultimately contribute to the uprising?