Listen to the article

A former schoolteacher armed with a radio and a force of Solomon Islander scouts became one of World War II’s most legendary coastwatchers, killing more than 50 Japanese soldiers and providing intelligence that helped save the Guadalcanal campaign. Donald Gilbert Kennedy’s men gave early warning of every Japanese air attack on Guadalcanal from Rabaul over the course of 10 months in 1942 and 1943, allowing Marine and Navy fighters to scramble and meet the incoming raids. His exploits earned him both the British Distinguished Service Order and the U.S. Navy Cross.

U.S. Admiral William Halsey later declared that coastwatchers saved Guadalcanal and the Battle of Guadalcanal saved the Pacific.

The Battle of Guadalcanal

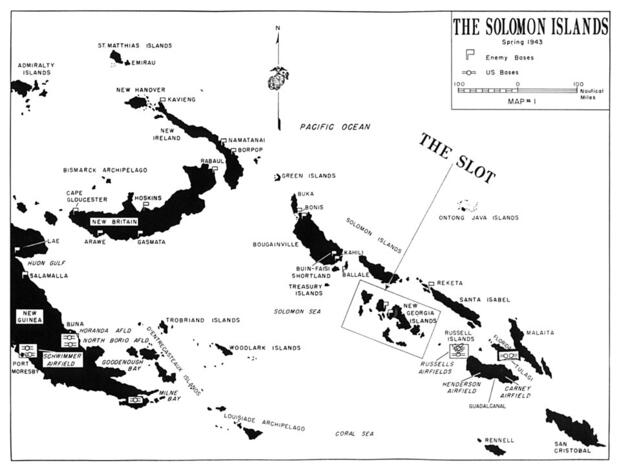

In the summer of 1942, Japanese construction crews were building an airfield at Lunga Point on Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands. American intelligence learned of the threat from Allied observers scattered throughout the Pacific islands. A Japanese airbase on Guadalcanal would allow enemy bombers to patrol shipping lanes to Australia and threaten Allied positions throughout the region.

On Aug. 7, 1942, U.S. Marines stormed ashore and captured the nearly completed airfield, renaming it Henderson Field after a Marine aviator killed at Midway. The Japanese immediately began a six-month campaign to recapture it. They launched near-daily bombing raids from their major base at Rabaul, 560 miles northwest. The round-trip flight took eight hours, pushing Japanese pilots to their limits.

If Japanese bombers arrived at Henderson Field unannounced, they could destroy American aircraft on the runway and kill Marines in their defensive positions. The Marines needed advance warning to scramble fighters and prepare their defenses. Without it, Henderson Field could fall and the Marines would be isolated without quick air support.

The coastwatcher network in the region provided that warning.

The Coastwatchers

The Australian coastwatcher organization began in the 1920s as a network of plantation owners, traders and government officials positioned across multiple remote Pacific islands in strategic locations. In 1939, Lieutenant Commander Eric Feldt of the Royal Australian Navy expanded the network, recruiting volunteers who knew the islands and could survive in hostile territory.

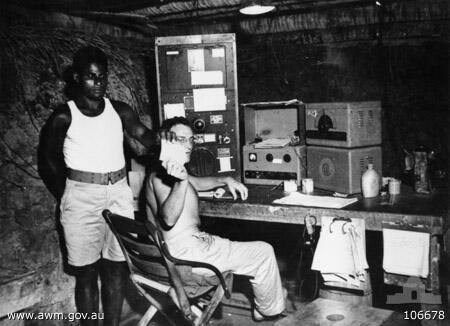

Feldt equipped his coastwatchers with teleradios, heavy radio transceivers that could send and receive voice and Morse code transmissions. The devices weighed several hundred pounds with their batteries and required regular maintenance in the humid tropical environment. Coastwatchers had to hide these bulky radios in the jungle while staying mobile enough to avoid Japanese patrols.

Feldt code-named his operation “Ferdinand” after a children’s book about a bull who preferred smelling flowers to fighting. The name alluded to the organization’s role as intel gatherers instead of warriors as coastwatchers were to remain hidden, observe enemy movements, and radio intelligence to Allied forces. They were not to engage in combat or draw attention to themselves. The Japanese executed captured coastwatchers as spies.

By late 1941, Feldt had positioned coastwatchers throughout the Solomon Islands, monitoring Japanese movements. When Japan swept through the Pacific after Pearl Harbor, many coastwatchers found themselves suddenly operating behind enemy lines. In April 1942, Feldt secured military commissions for them as officers in the Royal Australian Navy Volunteer Reserve to provide some legal protection if captured and ensure their families received benefits if they were killed.

The coastwatchers spotted Japanese aircraft or ships, radioed coded warnings to Allied headquarters, and then headquarters relayed the information to forces in the area. For Henderson Field on Guadalcanal, this meant coastwatchers on islands like Bougainville and New Georgia could observe Japanese bomber formations departing Rabaul and warn the Marines.

The warnings gave American fighters 30 to 60 minutes to take off and gain altitude before the Japanese arrived. Even as Japanese infantry overran the islands, the coastwatchers continued their job, avoiding the patrols as much as possible.

However, one coastwatcher violated Feldt’s doctrine completely.

The Former Teacher Leads a Guerilla Army

Born in March 1898 near Invercargill, New Zealand, Kennedy served in WWI with the 10th North Otago Company.

He later earned his teaching certificate and spent years educating Pacific Islander children at the Banaban School on remote Ocean Island in the Gilbert Islands. In 1940, he transferred to the British Solomon Islands Protectorate headquarters at Tulagi as a district officer, responsible for administering territories across the island chain.

When Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, Kennedy volunteered for coastwatcher duty rather than evacuate with most other civilians. As Japanese forces swept through the Solomons in early 1942, he used a small motorboat to establish his first station at Mahanga on Santa Isabel Island on April 20. His intelligence reports about Japanese shipping movements off Santa Isabel enabled the evacuation of Tulagi before enemy troops invaded on May 3.

Kennedy radioed a defiant message to every village under the threat of invasion, “These islands are British and they are to remain British. The government is not leaving. Even if the Japanese come, we shall stay with you and in the end they will be driven out.”

After someone betrayed his motorboat’s location, Kennedy escaped to Segi on New Georgia’s southern coast in July 1942. He took over the abandoned Markham Plantation, turning it into a fortified military compound protected by treacherous channels and coral reefs.

Building an Army in the Jungle

While other coastwatchers hid alone with native scouts for protection, Kennedy recruited approximately 30 Solomon Islander fighters from the British Solomon Islands Protectorate Defence Force and armed them with captured Japanese weapons. Sergeant William Bennett became his tactical coordinator.

Kennedy hid his teleradio 800 meters into the bush and positioned reserve stations up to 16 kilometers deep in the jungle. Multiple layers of scouts formed protective screens while others penetrated enemy territory by the use of canoes. Despite orders to remain hidden, Kennedy’s men routinely ambushed unsuspecting Japanese troops.

Kennedy’s scouts also monitored Japanese aircraft departing Rabaul and radioed warnings to Henderson Field. Warning messages gave the Cactus Air Force enough time to scramble fighters. This early warning happened repeatedly, allowing American pilots to meet Japanese formations in the sky off the coast of Guadalcanal rather than being bombed on the ground.

His shipping reports allowed Allied naval forces to ambush enemy supply runs in “The Slot.” Kennedy’s station became one of the most productive intelligence posts in the entire Solomon Islands.

The Guerilla War Behind Enemy Lines

Bennett later recalled their operational planning sessions, “Every time a report came Kennedy and I would sit down and plan what to do and how to do it. We only picked those Japanese patrols that we knew we could kill.”

Kennedy’s scouts tracked enemy patrols through the jungle, sometimes identifying Japanese soldiers by their distinct smell before visual contact. On one mission, Bennett and his men followed six Japanese soldiers through the bush for hours, waiting for the perfect moment. At dawn, they attacked.

“We shot them all,” Bennett recalled. “We buried them properly, took their guns, their radios, and documents. Kennedy was very happy.”

When Japanese patrols approached Segi, Kennedy’s forces systematically ambushed and eliminated them to protect the compound’s location. After the Japanese established a base nine miles away at Viru and sent a 25-man patrol to find Segi, Kennedy’s scouts ambushed the group at night and dispersed it.

Kennedy armed his commandeered schooner Dadavata with a .50-caliber machine gun, converting the small vessel into a gunboat. When a Japanese whaleboat began reconnoitering islands in the Marovo Lagoon too close to his position, Kennedy attacked and sank it.

Throughout these operations, Kennedy’s forces killed at least 54 Japanese soldiers. Kennedy himself and two Solomon Islander scouts sustained wounds but continued fighting.

Kennedy also established a rescue network for downed airmen, offering Solomon Islanders a bag of rice and a case of tinned meat for each pilot delivered to Segi, regardless of nationality. This bounty system resulted in 22 American airmen being rescued as well as 20 Japanese pilots captured. All of them were collected by Allied transport planes.

However, Kennedy’s active combat missions and the Ferdinand philosophy of remaining hidden created tension with other coastwatchers. Despite this, his intelligence gathering and guerilla missions became a major detriment to Japanese troops operating in the region.

The Rescue and the End of Kennedy’s Operations

In early June of 1943, Japanese troops aimed to put a stop to Kennedy’s coastwatcher team. Japanese General Noboru Sasaki knew that they would assist an American invasion of the island. On June 17, Japanese reinforcements arrived at Viru Harbor to assault Segi.

Kennedy radioed Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner on June 18 to warn him of the impending assault. Turner moved the invasion date up nine days, knowing any further delay would endanger Kennedy and his men. Companies O and P from the 4th Marine Raider Battalion under Lieutenant Colonel Michael Currin landed at Segi Point on June 21, saving Kennedy just before the Japanese battalion arrived.

The Marines discovered a fortified base with an arsenal, prisoner-of-war cage and comprehensive maps. Kennedy immediately briefed the officers on Japanese positions and the terrain. His knowledge proved invaluable to the Americans.

Within hours, the 20th, 24th and 47th Naval Construction Battalions began building a fighter airstrip. Despite bad weather and poor soil, the Seabees completed a 3,300-foot coral runway on July 18. The Segi airfield provided crucial support for the assault on Munda Point, which fell Aug. 5. The base Kennedy defended for nearly a year helped break Japanese control of the island chain.

Kennedy’s Legacy

Kennedy’s wartime service earned exceptional recognition from the Allied nations. Britain awarded him the Distinguished Service Order. The United States presented him the Navy Cross with a citation praising his extraordinary heroism in leading numerous skirmishes that destroyed or captured many Japanese troops, machine guns and barges with negligible injury to his force.

However, his methods proved controversial. Historical records indicate he earned a reputation for harsh treatment of subordinates and islanders who defied his authority. Others argue this was because of the immense pressure he faced while operating behind enemy lines.

His aggressive patrols violated the Ferdinand philosophy that other coastwatchers lived by. Yet, Admiral Halsey’s assessment of the coastwatchers’ efforts shows that all of them, including Kennedy, were vital to the success on Guadalcanal and the rest of the region.

Kennedy died in Whangarei, New Zealand, in 1976 at age 77. His wartime papers and documents are preserved at the University of Auckland.

The former teacher who became a guerrilla leader represents the type of unconventional warfare that characterized Pacific Island combat. It also shows that determined individuals with skillful locals and outside support can impact entire strategic operations. While Kennedy is remembered as one of the most legendary coastwatchers, the Solomon Islanders and men like Sergeant Bennett under his command fought valiantly against the Japanese and helped secure victory in the region.

Allied operations in the Solomon Islands were the first major setbacks for Japanese forces in WWII. Coastwatchers proved invaluable to the invasion fleets as well as the Marines and troops fighting in the jungle.

Story Continues

Read the full article here

18 Comments

The fact that Admiral William Halsey declared that coastwatchers saved Guadalcanal and the Battle of Guadalcanal saved the Pacific highlights the significant impact of these unsung heroes of World War II.

The Japanese airbase on Guadalcanal would have allowed enemy bombers to patrol shipping lanes to Australia and threaten Allied positions throughout the region, making the capture of the airfield by U.S. Marines a pivotal moment in the war.

This strategic location was indeed critical, and the Allies’ ability to secure it was a significant blow to Japanese expansion plans.

It’s remarkable that the coastwatchers were able to survive in hostile territory, hiding their radios in the jungle while staying mobile enough to avoid Japanese patrols, and still manage to send and receive critical information.

The capture of the airfield at Lunga Point on Guadalcanal by U.S. Marines on August 7, 1942, was a significant moment in the war, and the subsequent defense of the airfield against Japanese counterattacks was made possible by the coastwatchers’ early warnings.

The fact that Donald Gilbert Kennedy’s men gave early warning of every Japanese air attack on Guadalcanal from Rabaul over the course of 10 months in 1942 and 1943 is a testament to their bravery and strategic importance, allowing Marine and Navy fighters to scramble and meet the incoming raids.

This early warning system was crucial in saving countless lives and turning the tide of the battle in favor of the Allies.

The experience of Corporal Donald Gilbert Kennedy serving in the Army during World War I likely influenced his later actions as a coastwatcher, and his ability to lead a guerrilla army behind Japanese lines was likely shaped by his earlier military service.

The coastwatcher network, which began in the 1920s as a network of plantation owners, traders, and government officials, played a vital role in providing advance warning of Japanese air attacks, and their efforts were instrumental in the Allied victory.

The code-named operation ‘F’ led by Lieutenant Commander Eric Feldt was a testament to the ingenuity and bravery of the coastwatchers, who risked their lives to provide vital intelligence to the Allies.

The Australian coastwatcher organization, led by Lieutenant Commander Eric Feldt, was a crucial component of the Allied effort, and their bravery and sacrifice should be remembered and honored.

I’m curious about the specifics of the teleradios used by the coastwatchers, which weighed several hundred pounds with their batteries and required regular maintenance in the humid tropical environment – how did they manage to keep them operational?

The coastwatchers had to be resourceful and skilled in maintaining these bulky radios, often relying on local knowledge and improvisation to keep them functioning.

I’m skeptical about the claim that the coastwatchers saved Guadalcanal – while they certainly played a crucial role, it was a complex and multifaceted campaign that involved many different factors and contributors.

While it’s true that the coastwatchers were not the sole factor in the Allied victory, their contributions were undoubtedly significant and deserve recognition.

The fact that Donald Gilbert Kennedy was awarded both the British Distinguished Service Order and the U.S. Navy Cross for his bravery and service is a testament to the high regard in which he was held by both the British and American militaries.

The Battle of Guadalcanal was a turning point in the war, and the role of coastwatchers like Donald Gilbert Kennedy in providing intelligence and early warnings was instrumental in the Allied victory, allowing them to prepare defenses and scramble fighters.

It’s astonishing that a former schoolteacher like Donald Gilbert Kennedy could lead a guerrilla army behind Japanese lines in the Solomon Islands, killing more than 50 Japanese soldiers and providing intelligence that helped save the Guadalcanal campaign.