Listen to the article

When Captain William H. Dabney arrived at the 3rd Marine Division personnel office in Vietnam in the summer of 1967, he checked the list of available company commands. He picked the one as far away from headquarters and as close to the North Vietnamese border as possible.

It was exactly what the son-in-law of Lieutenant General Lewis “Chesty” Puller would have done. Soon after, the Marine officer was leading his men in a desperate fight against an overwhelming enemy force during the Siege of Khe Sanh.

Joining the Marine Corps

William Howard Dabney was born in St. John, New Brunswick, Canada, on September 28, 1934. He was raised in Panama and Gloucester County, Virginia, graduating from Christchurch School in 1953. He attended Yale for a year before enlisting in the Marine Corps in 1954.

Dabney trained at Parris Island, then served with the 3rd Marine Division in Japan, reaching sergeant before being discharged in 1957. That same year, while attending a funeral in uniform, he met Lieutenant General Chesty Puller, the most decorated Marine in history.

Puller never missed an opportunity to chat with a fellow leatherneck. He asked Dabney to join him for lunch the following day. During their conversation, Mrs. Puller observed that the young sergeant stood six-foot-four and thought he might be a good match for their daughter, Virginia, who was also tall.

Dabney enrolled at VMI in 1957, majored in English, played soccer, and held his rank all three years. He graduated with the Class of 1961 and was commissioned into the Marine Corps.

In September of that same year, he married Virginia McCandlish Puller. A friend observed that “it took a hell of a man even to ask for the hand of Virginia Puller, the daughter of General Lewis B. ‘Chesty’ Puller, and a hell of a man to meet with his approval. Bill was that man.”

Dabney, now an infantry officer, eventually got orders to return to the 3rd Marine Division, this time in Vietnam.

On his first day as headquarters company commander, his unit came under massive artillery fire. He spent the day conducting combat triage, designating which Marines could be saved and which could not.

He recalled it as a rough first day.

Baptism by Fire

In December 1967, Dabney took command of India Company, 3rd Battalion, 26th Marines. On December 26th, he led his men to the top of Hill 881 South, a treeless mountaintop about four miles west of Khe Sanh Combat Base. The area had been heavily contested by Marines and communist troops the year prior.

Dabney later compared the terrain to House Mountain near VMI, roughly the same dimensions and elevation. Cliffs dropped sharply on three sides, with only one approach offering a gentler slope. His position was the farthest west and north of any American command in South Vietnam. Laos was only eight miles to the west. A battalion of North Vietnamese Army regulars was digging in on Hill 881 North, two kilometers directly across from Dabney’s position.

On January 20, 1968, now commanding India Company, Dabney led his men on a reconnaissance-in-force toward Hill 881 North. They waded through elephant grass that towered over their heads and left cuts on any exposed skin, all while navigating pre-dawn darkness and thick fog. They walked straight into an NVA battalion.

The lead platoon took heavy fire. Dabney moved to the front and found his men pinned down with mounting casualties. He sent the reserve platoon to assist. Both platoon leaders were killed. A medical evacuation helicopter was shot down trying to reach the wounded.

Dabney called in artillery, air support and napalm danger close. He ordered his men to withdraw but stayed behind to provide covering fire. When one platoon became pinned down after seizing its objective, he advanced across 500 meters of open terrain to help them, repeatedly exposing himself to pinpoint NVA automatic weapons positions. His actions destroyed the heavy machine gun that had shot down the medevac aircraft.

India Company had stumbled into the opening act of the Tet Offensive.

The next morning, NVA forces launched coordinated attacks across the Khe Sanh area. A rocket slammed into the main ammunition dump at the combat base, detonating 1,500 tons of explosives. The 77-day siege had begun.

Mike Company joined Dabney on Hill 881 South. As senior officer, he assumed command of both units. His force numbered approximately 400 men, though casualties and lack of replacements sometimes dropped that to 250. They would not leave until April.

Into the Trenches

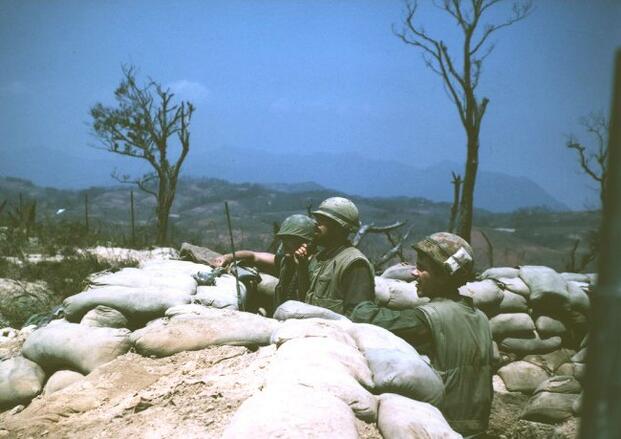

Dabney ordered his men to dig trenches around the entire perimeter. NVA snipers shot at the men constantly. Mortars and artillery hit the hill daily.

The Marines had three 105mm howitzers, two 106mm recoilless rifles, and 60mm and 81mm mortars. They had razor wire and claymore mines. But the enemy had overwhelming numbers.

Hill 881 South was cut off from ground resupply. Everything came by helicopter and each craft drew enemy fire.

Dabney calculated he had 25 seconds to unload or load a helicopter before NVA mortars landed. His men watched as their commanding officer sprinted to every chopper, directing unloading operations while fully exposed, cigar clenched in his teeth. Seven helicopters were shot down trying to resupply his position.

“There are only two ways to get off this hill,” the troops said. “Either fly off or get blown off.”

The conditions were brutal. Water was so scarce the Marines could not bathe or shave. Dabney refused to request extra water for hygiene, he instead focused on extra ammunition and replacements.

“People who write regulations have never been anyplace like 881S,” he later said.

Giant rats infested the position, biting Marines as they slept. Sanitation was primitive. The men devised a crude system of using empty artillery powder canisters as latrines, and when one was full, the last user would drop in a live grenade, seal the lid, and send it rolling down the hillside toward NVA positions. On some nights, a blast followed by screams confirmed the improvised weapon had found its target.

One night, a Marine approached the company gunnery sergeant in the trench line. He was nervous, but felt obligated to report what he had detected. He told the gunny he was reluctant to admit he knew what marijuana smelled like, but he had been smelling pot in the wind blowing toward them from the north, and the smell was getting stronger.

There were no Marine units to the north. Relying on the Marine’s instincts about the location, Dabney ordered more than 1,000 rounds of mortars and mixed-fuse artillery into the darkness. The NVA made no attacks that night.

Turnover in the trenches approached 90 percent, meaning many men were strangers to their fellow defenders. Fresh troops would exit the helicopter and stand motionless, unsure where to go, making themselves easy targets.

Dabney stationed experienced Marines near the landing zone with orders to grab new arrivals and tackle them into the nearest fighting hole before enemy rounds found them. Even a visiting battalion commander received the same rough welcome.

PFC Ernest Webb saw morale slipping and wrote to his pastor back home describing their situation. The pastor came up with “Operation We Care,” as his church and other organizations responded. Care packages poured onto the hill, some containing liquor concealed in plastic baby bottles, the nipples turned inward so nothing sloshed when mail handlers inspected the packages.

Delis and stores back home sent snacks and food. The letters and packages were sometimes riddled with shrapnel or soaked in whiskey from broken bottles in care packages. Chocolate chip cookies soaked in bourbon became an unexpected treat.

At one point, a helicopter dropped a supply crate but left in a hurry as the NVA opened fire. The Marines waited until nightfall to run and open the crates, only to realize it was full of ice cream that had already melted. Regardless, morale was boosted.

The Marines also enforced their own discipline regarding drugs. When replacements or Marines returning from treatment brought marijuana back to the hill, their fellow Marines responded immediately and violently. Their lives depended on the alertness of their comrades, and they would not tolerate anything that compromised it.

One evening, Dabney walked the trench lines to check on his men. He paused beside a Marine with a transistor radio tuned to Armed Forces Radio. The announcer broke in with a “Special Announcement.” The Marines expected news of a major victory or a truce.

The announcement informed listeners that an officer’s tennis tournament in Saigon had been rescheduled.

The Marine looked at Dabney. “Skipper, are we and those fucking people in Saigon fighting the same war?”

The Super Gaggle

The single-helicopter resupply system was killing Marines and aircrew. In the first four weeks, six helicopters were shot down on Hill 881 South alone. Dozens of Marines were killed or wounded during resupply.

Dabney contributed some ideas to what became Operation Sierra, better known as the Super Gaggle. On February 24, 1968, Marine aviators launched the first coordinated mass resupply.

Four A-4 Skyhawk jets appeared first, two on either side of the hill, attacking antiaircraft positions with Zuni rockets. Two more dropped cluster bombs and 250-pound bombs in the valleys. Two to four more dropped napalm along both sides of the hill to discourage NVA soldiers who would lie on their backs and fire AK-47s into helicopter bellies. Two final A-4s laid smoke screens.

Dabney’s mortars fired white phosphorus rounds at known anti-aircraft sites. Every Marine in the trench line hurled a grenade as far down the hillside as he could throw. Then ten CH-46 Sea Knight helicopters appeared in two strings of five, swooped in simultaneously, dropped cargo nets packed full of supplies, then departed before the smoke cleared.

Lieutenant Colonel Al Chancey, a helicopter pilot who flew the missions, later recalled the significance.

“The courage and determination of his Marines on 881S was a true inspiration to those of us who flew the Super Gaggle,” Chancey said. “We understood that we were their lifeline and that we could not fail them.”

In the seven weeks after Super Gaggle began, no helicopters were shot down on Hill 881 South. Casualties during resupply dropped to about 20 wounded and zero killed.

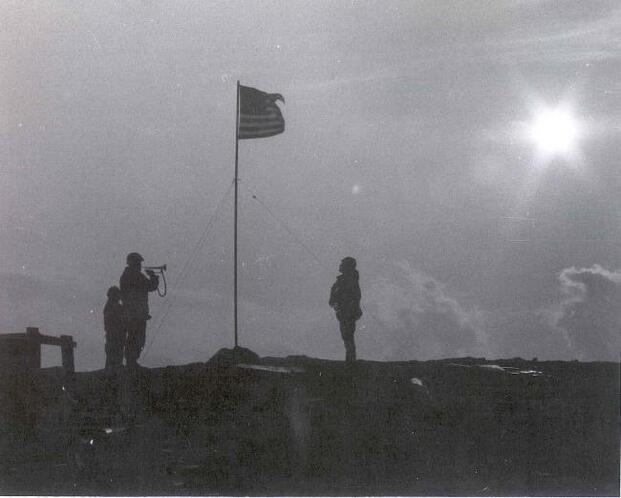

Raising the Colors

In early February, Dabney started a daily ritual that would become legendary among Khe Sanh veterans.

Every morning, three volunteers dashed from their fighting holes to a makeshift flagpole fashioned from a radio antenna. Two hoisted the colors while the third played ‘To the Colors’ on a battered bugle, standing at attention even as enemy rounds cracked overhead. Each evening, the Marines lowered the flag.

The display enraged the NVA, who dug in on Hill 881 North and fired at the flag party almost daily. Dabney noted each muzzle flash revealed a position his forward air controllers could mark for airstrikes.

The Marines never lacked volunteers for the detail. When a Marine died on the hill, the flag that had flown that day was often folded and sent to his family. Americans across the country mailed replacements, Dabney noted they amassed a stockpile. One World War II widow shipped her late husband’s burial flag, writing that he would have preferred it see service again rather than sit forgotten in storage.

On the day of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination, a Black NCO approached Dabney and asked that the flag be flown at half-mast. Dabney understood but explained that it was vital that the flag remain as is to bolster morale and continue irritating the enemy. The NCO agreed and even volunteered for flag detail the next morning.

Corporal Robert Arrotta, a radio operator, became the hill’s forward air controller after the original FAC was wounded on the first day. Dabney told the battalion he did not need a replacement. Arrotta controlled approximately 300 close air support missions during the siege. The troops called him “The Mightiest Corporal in the World.”

Lance Corporal Molinau “Mike” Niuatoa served as Arrotta’s spotter. The American Samoan had scored 241 out of 250 with his M-16 in boot camp and had the patience to track enemy positions for hours. After two weeks of careful observation, he detected the telltale flash of NVA 130mm artillery originating far to the west, likely inside Laos.

Niuatoa told the forward air controller to adjust from the initial bomb’s impact point. Over the next hour, using multiple flights of attack aircraft and Niuatoa’s corrections, they destroyed four enemy guns. Niuatoa earned a Bronze Star for his actions.

The Cost of Holding Hill 881 South

By April 1968, relief forces, including the Army’s 1st Cavalry Division, reached Khe Sanh, effectively lifting the siege. According to Dabney, it seemed as if the enemy simply gave up and left the area after that.

Lt. Col. John C. Studt transferred Dabney to command of a Provisional Weapons Company and ordered him to hold the hill while the 3rd Battalion moved to secure 881 North. Soon after, Dabney led his remaining men off the hill, the first break they had in almost three months of combat.

Dabney had lost more than 50 percent of his command. Forty-two Marines were killed, and nearly 200 were wounded. His Navy Cross citation noted that “total casualties during the siege were close to 100 percent” when counting replacements. Dabney himself weighed 155 pounds when he returned to Quang Tri. His normal fighting weight was 205.

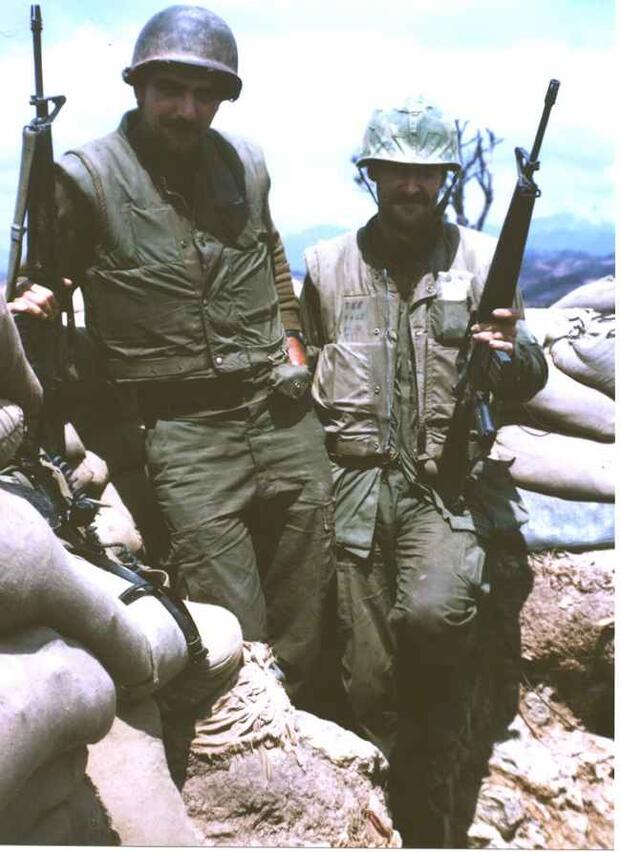

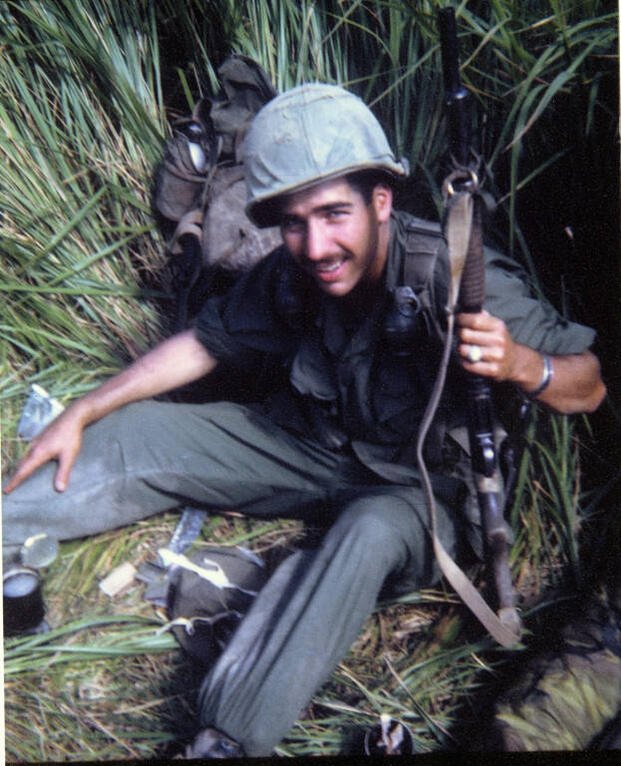

Staff Sergeant Karl Taylor, his 1st Platoon sergeant on Hill 881 South, would earn the Medal of Honor later that year during Operation Meade River. In a photograph from the hill, Taylor and Dabney stand together, filthy and unshaven, having just survived one of the deadliest portions of the Siege of Khe Sanh.

The Delayed Honor

Dabney received the Silver Star for the initial firefight on January 20. He was also nominated for the Medal of Honor for his heroic leadership on Hill 881 South throughout the battle. A senior officer downgraded the recommendation simply because Dabney had not been wounded during that time, though he earned a Purple Heart later.

Unfortunately, the paperwork for his Navy Cross was lost in a helicopter crash. He did not receive the award until 2005.

The citation concluded, “Colonel Dabney contributed decisively to ultimate victory in the Battle of Khe Sanh, and ranks among the most heroic stands of any American force in history.”

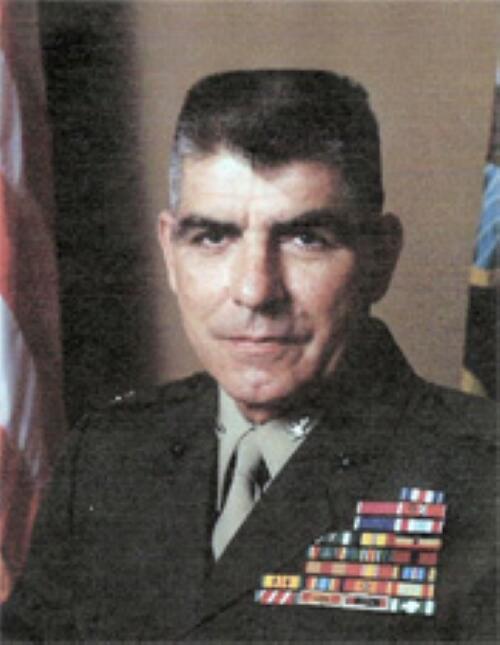

Dabney returned to Vietnam for a second tour from 1970 to 1971 as a senior adviser to a Vietnamese Marine battalion. He later commanded a Marine battalion and a regiment, served at the Pentagon and finished his career as Commandant of Cadets at VMI from 1989 to 1990. He finally retired after 36 years of service.

He settled in Lexington, Virginia, near VMI. He and his men held reunions for decades.

Colonel Tom Ripley, a fellow Marine and Navy Cross recipient, described his friend simply.

“This is a man who saw the world in black and white,” Ripley said. “He made no excuses for his absolute approach to all things. His delivery was direct without exception. He was the kind of person that you did not ask a question if you couldn’t stand the answer.”

When asked about his relationship with Chesty Puller, Dabney was characteristically blunt about whether he called his father-in-law “Dad.”

“Hell no,” Dabney replied. “He was either ‘General’ or ‘Sir.'”

Bill Dabney died on February 15, 2012, at age 77. His son Lewis delivered the eulogy.

“He demanded good effort and absolute integrity,” Lewis said. “Nothing less was tolerated, but with these high expectations, however, came deep love and commitment.”

Read the full article here

5 Comments

This is very helpful information. Appreciate the detailed analysis.

I’ve been following this closely. Good to see the latest updates.

Good point. Watching closely.

Interesting update on This Marine Married Chesty Puller’s Daughter and Was Recommended for the Medal of Honor at Khe Sanh. Looking forward to seeing how this develops.

Solid analysis. Will be watching this space.