Listen to the article

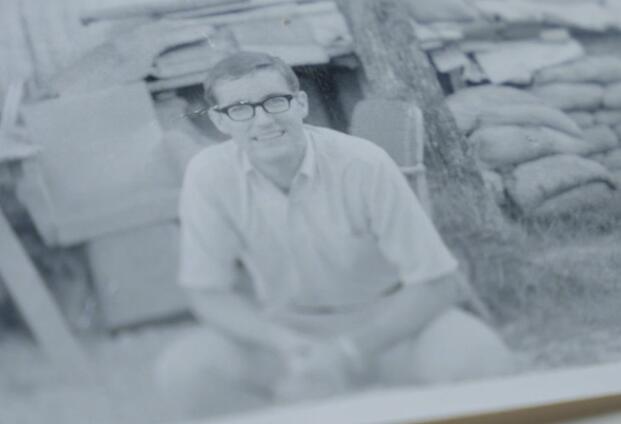

It’s been almost 58 years since Army veteran Robert Hendricks witnessed some of the worst moments of the Vietnam War, but those stark memories remained burned into his subconscious.

Hendricks, who was drafted into service in 1967, was in Vietnam when the infamous Tet Offensive began in January 1968 and saw firsthand the damaging effects of napalm, a mix of various acids, soaps, and aluminum salts used to thicken gasoline that was used in flamethrowers and bombs. The thick substance, almost jelly-like, could be launched further and burn more slowly than other foliage-killing substances.

After receiving his draft notice in the mail from Selective Service, Hendricks reported to Fort Ord, California for basic training then went to Fort Holabird in Baltimore, Maryland for military intelligence school.

“I think everyone who was graduating knew exactly where we were going,” Hendricks told Central Oregon Daily News. “It was either language school in Texas or straight to Vietnam, and mine was straight to Vietnam.”

Hendricks reported to Soc Trang, “way down in the Mekong Delta.” His unit was assigned to liaise with members of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam and the Vietnamese Marine Corps to gather valuable information on recent hostilities and enemy positions.

Surviving the Tet Offensive

Then came the Tet Offensive. Jan. 31, 1968. Hendricks calls it the most disturbing period during his time in Vietnam. The North Vietnamese military mounted a series of attacks throughout South Vietnam. Hendricks was bunking in a small blockhouse with another soldier when the assault began around 3 a.m.

“We began to creak open the front door, and you could see tracers going back and forth, and we both knew that we were in it, and we had no clue who was shooting or where they were shooting from, other than watching the tracers,” Hendricks said.

The veteran recalled having an eerie feeling when dawn arrived, and he couldn’t hear any noise outside in the village.

“There were no children laughing and screaming and what have you,” he said. “And we weren’t sure whether or not the village had actually been captured. And then for the next 72 hours, it was waiting for an all-clear so that we could get to the airbase.”

Before they could leave their location, however, Hendricks witnessed “the most horrific thing I’ve ever seen.” The U.S. Air Force used two F-100 Super Sabres (supersonic fighter jets) to clear the roadway. Hendricks said they dropped multiple 500-pound bombs before heading out, and then a third plane came and dropped 500 pounds of napalm before leaving.

The experience shook the young Army soldier.

Never Again

“I had never seen napalm in my life, and I never want to see it again,” he said.

When Hendricks and his bunkmate finally received an all-clear message that it was safe to travel to the Soc Trang airbase, they had to walk through the recently napalmed area. It was unlike anything he had seen before and opened his eyes to the horrors of war.

“That was disturbing,” he said. “You saw some bodies that were still smoking, and you had no clue if they were Viet Cong or if they were simply civilians.”

Those haunting images have stayed with him for almost six decades. Through the years, Hendricks has pondered the mental toll on a person seeing a body – or whatever is left of it after a bombing – roasting in the oppressive 100-degree heat of the Mekong Delta. Like so many other soldiers in Vietnam, the war had hardened him somewhat, but it didn’t cause him to lose his humanity, his empathy for others.

“It occurred to me that one body lying there—that was somebody’s father, somebody’s brother, somebody’s son. But there he is,” Hendricks said. “He had a history just like I did. It took some time to adjust to that.”

While he hated being in Vietnam, Hendricks was sensitive enough to realize the enemy soldiers he was battling every day were also people just like him. He felt for the people of Vietnam, an ancient civilization that simply wanted to be left alone.

“In one sense, I appreciated that experience, however dreadful it was—a real education in foreign affairs and human affairs,” he said.

Story Continues

Read the full article here

16 Comments

It’s disturbing to think that Hendricks and his fellow soldiers had to wait 72 hours for an all-clear before they could leave their location, not knowing whether the village had been captured or not, and facing the uncertainty of their own safety.

The use of napalm during the Vietnam War, as described by Hendricks, raises important questions about the ethics of warfare and the need for international agreements to regulate the use of such weapons.

The fact that Hendricks was drafted into service in 1967 and sent straight to Vietnam after basic training and military intelligence school underscores the rapid deployment of soldiers during the war and the lack of preparation for the harsh realities they would face.

The use of F-100 Super Sabres to clear the roadway, dropping 500-pound bombs and napalm, is a testament to the intense violence and destruction that occurred during the Tet Offensive, and Hendricks’ eyewitness account provides a personal perspective on the events.

The fact that Hendricks had never seen napalm before and was deeply affected by its use raises questions about the adequacy of training and preparation for soldiers facing such extreme situations.

The fact that Hendricks and his fellow soldiers had to rely on tracers to gauge the direction of gunfire is a stark reminder of the intense and disorienting nature of combat during the Tet Offensive.

Hendricks’ experience of being bunked in a small blockhouse with another soldier during the Tet Offensive and their uncertainty about who was shooting and from where highlights the confusion and chaos of war.

The dropping of 500 pounds of napalm by a third plane, as witnessed by Hendricks, is a testament to the scale of destruction caused by such weapons and the need for greater consideration of their impact on civilians and the environment.

Hendricks’ account of his time in Vietnam, from basic training to his experiences during the Tet Offensive, provides a personal and nuanced perspective on the war and its effects on those who fought in it.

Hendricks’ statement that ‘I never want to see it again’ in reference to napalm is a powerful indictment of the devastating effects of such weapons and the need for greater consideration of their use in combat.

The long-term psychological impact of witnessing such events on soldiers like Hendricks cannot be overstated, and it’s essential to acknowledge the sacrifices they made and the difficulties they faced during and after the war.

Hendricks’ experience in Soc Trang, in the Mekong Delta, and his assignment to gather information on enemy positions, highlights the complexities and challenges of military intelligence work during the Vietnam War.

The image of a silent village, devoid of children’s laughter and screams, is a haunting reminder of the human cost of war and the impact on civilians, as described by Hendricks during the Tet Offensive.

The Tet Offensive, which Hendricks witnessed firsthand, marked a significant turning point in the Vietnam War, and his personal account provides a unique perspective on the events that unfolded during that time.

Robert Hendricks’ account of the Tet Offensive, which began on January 31, 1968, is a stark reminder of the devastating effects of war, particularly the use of napalm, which he described as a ‘jelly-like’ substance that could burn slowly and cause widespread destruction.

The fact that Hendricks witnessed the aftermath of napalm bombings, which left him shaken, highlights the need for greater awareness about the long-term consequences of using such weapons in combat.